Navigating the Regulatory Maze: Legal and Ethical Considerations for Child and Teen Business Owners in the Digital Age

The digital era has catalyzed an unprecedented surge in entrepreneurial spirit among children and teenagers, transforming the landscape of youth engagement and economic participation. Far from the traditional lemonade stand, today’s young innovators are leveraging technology and social media to launch diverse ventures encompassing e-commerce, content creation, application development, and social enterprises. This burgeoning trend of “kidpreneurs” and “teen entrepreneurs” signifies a profound shift in generational aspirations, with Generation Z widely recognized for its entrepreneurial drive. However, this exciting wave of youthful innovation is met with a complex array of legal and ethical considerations, demanding a delicate balance between fostering independent enterprise and safeguarding the well-being of minors.

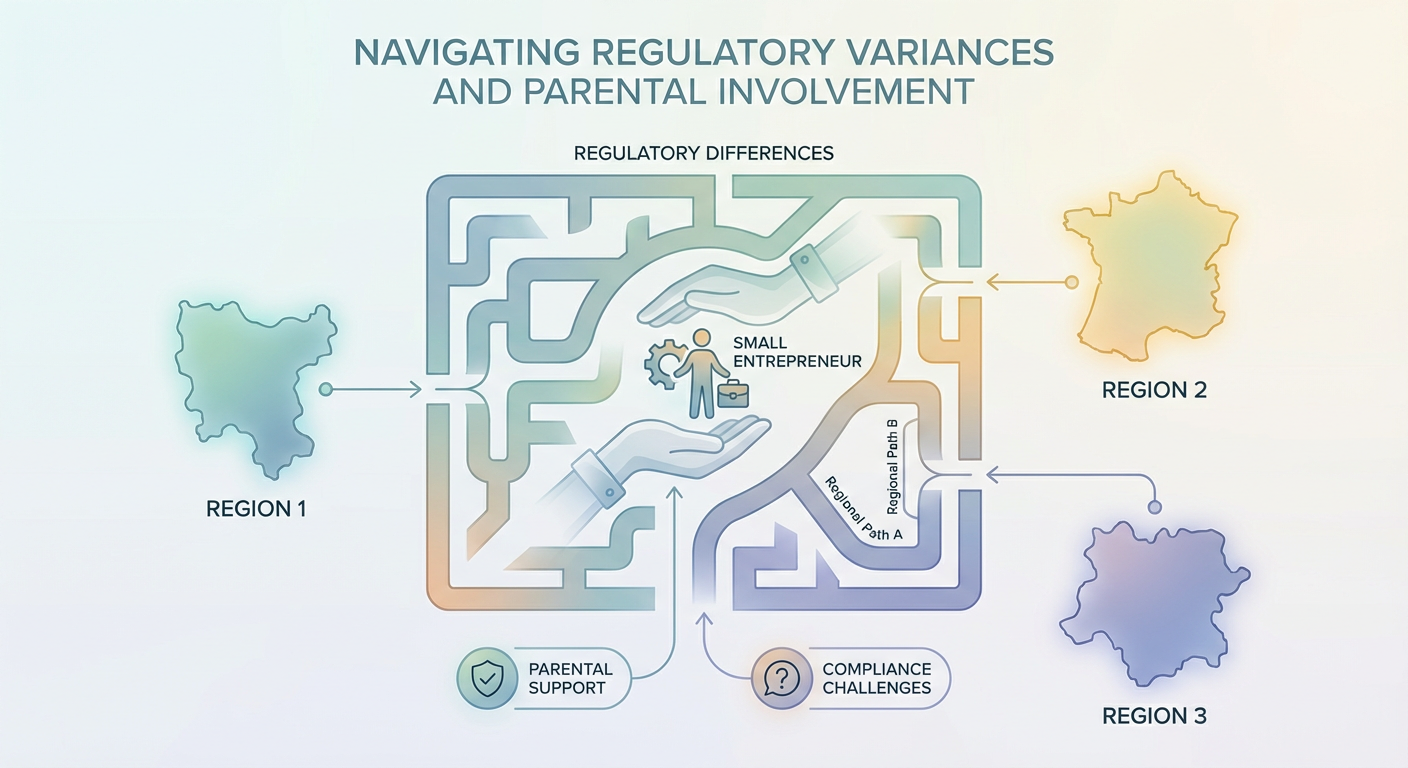

This comprehensive report delves into the intricate legal and ethical challenges confronting young business owners in the digital age. From the fundamental restrictions on minors’ contractual capacity to the nuanced regulations governing online platforms and data privacy (like COPPA and GDPR), we examine the multifaceted “regulatory maze” that aspiring youth entrepreneurs must navigate. We also explore critical ethical concerns, such as potential child labor, parental exploitation, and the psychological burdens of premature business responsibility, highlighting emerging regulatory responses and best practices designed to protect children while nurturing their entrepreneurial potential.

Key Takeaways

- Youth entrepreneurship is surging, with 75% of teens open to starting a business (up from 41% in 2018).

- Legal age restrictions (typically 18) pose significant barriers, requiring adult involvement for contracts and business formation.

- Regulations for minors in business vary drastically by jurisdiction, creating a complex global patchwork of rules.

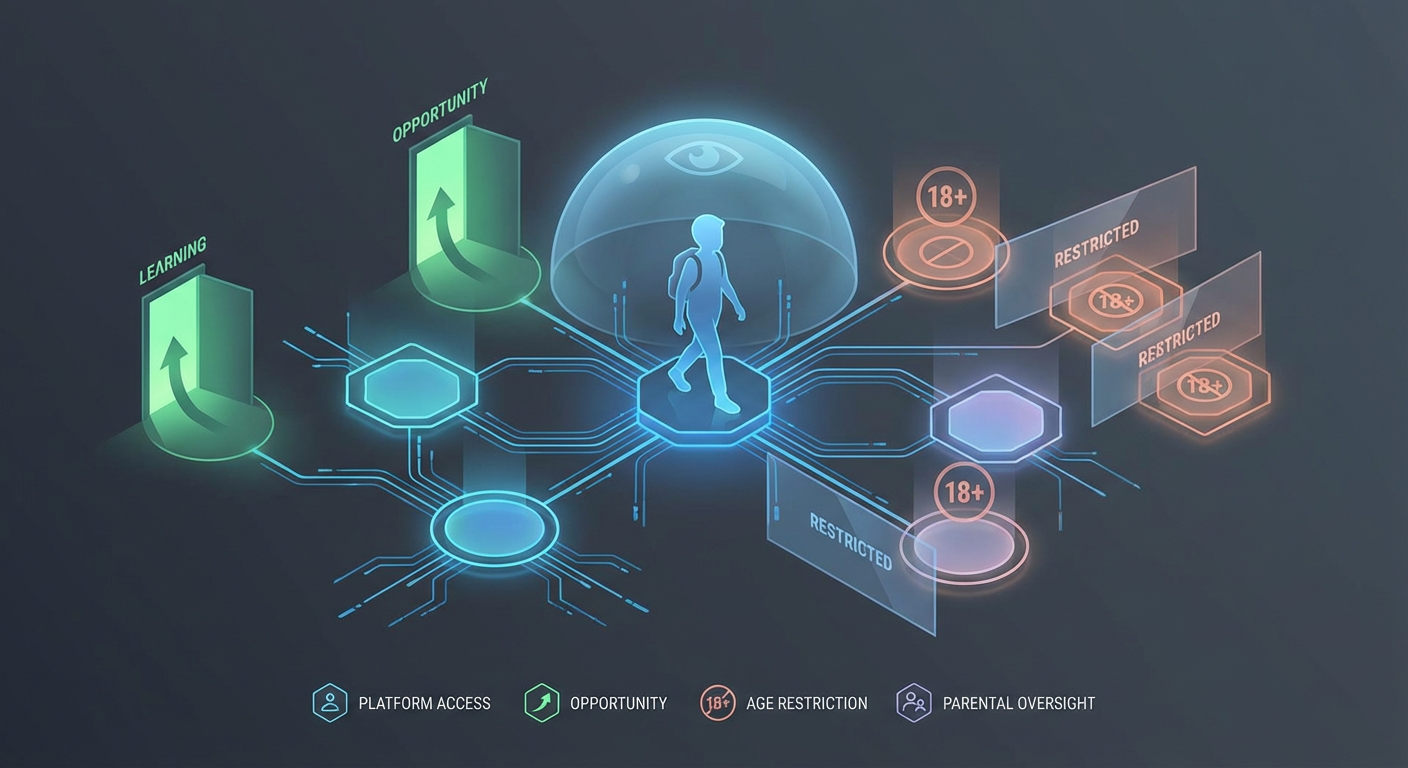

- Digital platforms often impose age restrictions, necessitating parental accounts for young online entrepreneurs.

- Data privacy laws (e.g., COPPA, GDPR) require parental consent for collecting minor’s data, impacting online business models.

- Ethical concerns abound, including potential child labor, exploitation, and the psychological impact of early business responsibility.

- New regulations are emerging to protect child influencers and curb exploitation, alongside initiatives promoting youth entrepreneurship education.

1. Executive Summary

The digital age has ushered in an unprecedented era of entrepreneurial ambition among adolescents and children, transforming the traditional landscape of youth engagement and economic participation. No longer confined to the lemonade stand at the end of the driveway, today’s young people are leveraging technology and social media to launch ventures that span e-commerce, content creation, application development, and social enterprise. This burgeoning trend of “kidpreneurs” and “teen entrepreneurs” represents a significant shift in generational aspirations, with Generation Z widely recognized as the most entrepreneurial demographic to date[3]. However, this exciting wave of youthful innovation is met with a complex array of legal and ethical considerations, demanding a delicate balance between fostering independent enterprise and safeguarding the well-being of minors. This executive summary provides a high-level overview of the rising phenomena of child and teen business owners, delves into the intricate legal and ethical challenges they encounter, and highlights emerging solutions and best practices.

The landscape of youth entrepreneurship is characterized by both soaring interest and significant practical hurdles. Recent surveys indicate a dramatic increase in entrepreneurial interest among teens, with 75% in 2022 expressing openness to starting a business, a sharp rise from 41% in 2018[1][2]. More than half of Gen Z globally plans to launch their own venture within the next decade[3]. While this ambition is widespread, the actual number of minors operating formal businesses remains relatively small in advanced economies. For instance, only about 5% of U.S. teens have started an entrepreneurial venture by high school age[5]. This gap between aspiration and realization often stems from the inherent legal complexities associated with minors engaging in business activities.

At the core of the regulatory maze lies the legal principle that most jurisdictions set 18 as the age of majority for contractual and business activities[6]. Minors generally lack the legal capacity to form binding contracts or incorporate companies without adult involvement[7][8]. This fundamental restriction means that critical business functions—such as registering a company, signing supplier agreements, opening bank accounts, or securing investments—typically necessitate a parent or legal guardian to act as a co-signer, legal owner, or establish specialized legal structures like trusts[9][10].

Compounding these challenges is a diverse and often inconsistent patchwork of regulations across different regions. While some jurisdictions, like South Africa, permit children as young as 7 to enter into contracts with parental consent[11], and the Netherlands provides a “limited legal capacity” framework for 16-17 year-olds[12], other nations, such as India and the UK, broadly consider agreements by under-18s unenforceable, effectively curtailing unsupervised business dealings[13]. Even within the United States, regulations vary significantly by state, with some historically prohibiting minors from company formation (e.g., Colorado) and others offering more flexibility under adult supervision (e.g., Texas, California)[14].

The digital realm, while lowering barriers to market entry for young entrepreneurs due to the accessibility of global customers and marketing channels, simultaneously introduces novel challenges. Online platforms, including payment processors like Stripe[15][17] and e-commerce sites such as Etsy[16][18], commonly impose age restrictions, often requiring users to be 18 or necessitating parental account holders. Furthermore, young online entrepreneurs must navigate stringent data and content regulations designed for minor protection. Laws like the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) in the U.S. and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe mandate parental consent for collecting personal data from users under specific age thresholds (e.g., 13 for COPPA, 16 for some GDPR contexts)[19][20]. Social media platforms, typically barring children under 13, present a complex ethical and legal grey area when teen content creators, who might not be legally old enough to agree to platform terms, build significant revenue streams[21][22].

Beyond legal frameworks, significant ethical concerns surround youth entrepreneurship. While celebrating “kidpreneurs,” critics voice apprehensions about potential child labor, parental exploitation, and the psychological burdens of premature business responsibility. High-profile cases, particularly involving family vloggers, have drawn attention to the risks of blurring the lines between hobby and work, and the imperative to protect minors from undue pressure or financial exploitation[23][24]. Safeguarding children’s education, well-being, and social development is paramount, requiring parental guidance and mentorship to ensure a balanced childhood[25]. Regulatory efforts are beginning to emerge to address these ethical dimensions, such as France’s 2020 law regulating “kid influencers” as child performers[26][27], and similar U.S. state laws requiring a portion of child influencer earnings to be set aside in protected accounts[28][29].

Recognizing the entrepreneurial spirit, governments are also gradually adapting archaic regulations. The proliferation of “lemonade stand laws” in over a dozen U.S. states since 2017 exemplifies a move to exempt incidental, low-revenue youth businesses from permits, acknowledging their value as learning experiences rather than formal commercial enterprises[30][31]. However, these exemptions often apply only to very small, informal operations, and full-scale youth businesses must still navigate standard regulations.

Crucially, overcoming the dual barriers of legal compliance and the fear of failure hinges on education and mentorship. Surveys reveal that two-thirds of teens are deterred by the prospect of business failure, and 55% feel insufficiently informed to succeed[32][33]. Nearly one-third express a need for mentorship, underscoring the vital role of educational programs, youth incubators, and industry role models in guiding aspiring young entrepreneurs[34]. The consensus among educators and policymakers is that with robust support systems – including educational resources, effective mentorship, and responsible parental involvement – young innovators can successfully traverse the regulatory landscape and realize their entrepreneurial potential.

1.1 The Resurgence of Youth Entrepreneurship

The 21st century has seen a significant revitalization of entrepreneurial ambitions among youth, diverging from previous generations’ career expectations. Generation Z, born between the mid-1990s and early 2010s, is particularly noted for its inclination towards entrepreneurship, often dubbed the “most entrepreneurial generation” to date[3]. This shift is not merely aspirational; it is visibly translated into a growing number of young people actively pursuing business ventures, frequently powered by digital tools and platforms.

1.1.1 Rising Entrepreneurial Ambition and Activity

The statistical evidence underscores this burgeoning trend. In 2018, market research indicated that 41% of teenagers were inclined to consider starting a business as a career option. By 2022, this figure had dramatically surged to 75%[1][2]. This nearly doubling of interest within four years highlights a profound shift in career paradigms. Looking ahead, a 2021 global survey of young people projected that 53% plan to launch their own business within the next decade. For older Gen Z individuals already engaged in the workforce, this ambition was even higher, with 65% aiming to start a venture within the same timeframe[35][36]. This indicates that direct exposure to the professional world further catalyzes entrepreneurial intent among this age group.

While interest is high, the actual conversion into operational businesses, especially formal ones, is more modest in advanced economies. For example, only approximately 5% of U.S. teenagers embark on an entrepreneurial venture by high school age[5], with a breakdown of 6% for boys and 4% for girls. This suggests that while the desire to innovate and create is strong, practical constraints and existing legal frameworks can impede widespread formal business formation among minors in these regions. Conversely, in developing economies, youth self-employment is a more prevalent phenomenon, often driven by necessity due to limited formal employment opportunities. Globally, about 25% of young people (aged 15–24) were self-employed or ran small businesses as per 2015 data[4]. However, in advanced economies like the European Union, only 6.5% of employed youth (20–29 years old) were self-employed in 2018, which is less than half the overall adult self-employment rate of 13.5%[37][38].

1.1.2 The Role of Technology and Shifting Mindsets

Several factors contribute to this rise in youth entrepreneurship:

- Digital Accessibility: The internet, social media, and readily available digital tools have lowered the barriers to entry for many types of businesses. A teenager can launch an e-commerce store, a content creation channel, or develop an application with minimal upfront capital and significant global reach[15].

- DIY Ethic: Gen Z exhibits a strong “Do It Yourself” (DIY) ethos, accustomed to self-learning through online tutorials and communities. This fosters confidence in initiating and managing projects independently[40][41].

- Influencer Culture and Role Models: The success stories of young influencers and startup founders, frequently amplified through social media, present entrepreneurship as an attainable and glamorous career path, inspiring peers to follow suit.

- Autonomy and Purpose-Driven Ventures: Modern youth often value autonomy, flexibility, and the ability to pursue work aligned with their values. Surveys indicate a strong inclination towards social entrepreneurship, with 58% of teens in 2022 willing to start a business addressing societal or environmental needs, even if it entails lower profits[42][43]. This generation seeks careers enabling “original thought and ideas,” a promise often fulfilled by entrepreneurial pursuits[44].

1.1.3 Implications and Opportunities

The increasing engagement of minors in business has broad implications:

- Educational Integration: Schools and educational institutions have an opportunity to integrate entrepreneurship education, incubators, and pitch competitions into curricula, transforming extracurricular ventures into valuable learning experiences. Organizations like Junior Achievement actively support this trend through programs like “JA Launch Lesson”[34].

- Economic Upside: Nurturing young entrepreneurs can foster future job creation, economic growth, and innovation, contributing to the overall competitiveness of economies.

- Parental and Mentorship Roles: Parents and guardians play a crucial role in supporting these endeavors, providing financial literacy, problem-solving skills, and ensuring a healthy balance between business and childhood. Mentorship is particularly vital, with 32% of teens indicating a need for a business owner role model[33].

1.2 Legal Barriers and Adult Engagement

Despite the enthusiastic surge in youth entrepreneurship, minors encounter significant legal impediments rooted in the foundational principles of contract and business law. These barriers necessitate diligent parental or guardian involvement to ensure legitimacy and mitigate risks.

1.2.1 The Age of Majority and Contractual Capacity

The primary legal hurdle is the “age of majority,” typically 18 years old in most jurisdictions. Below this age, individuals are deemed minors and generally lack the legal capacity to enter into binding contracts[6][7]. This protective measure, designed to shield minors from exploitation or detrimental agreements, inadvertently restricts their ability to conduct conventional business transactions. For example, a contract signed by a 17-year-old with a supplier or investor might be voidable, meaning the minor could unilaterally cancel the agreement without legal consequence. This uncertainty makes other parties hesitant to engage directly with underage entrepreneurs[39][22].

Table 1: Legal Age Thresholds for Business Activities

| Jurisdiction | Standard Age of Majority | Specific Provisions for Minors in Business |

|---|---|---|

| United States (most states) | 18 | Requires parent/guardian for contracts, business registration; few state-specific flexibilities (e.g., Texas, California)[14]; “lemonade stand laws” for micro-businesses[30]. |

| Netherlands | 18 | 16-17 year-olds can petition for “limited legal capacity” (handlichting) for business affairs[12]. |

| South Africa | 18 | Minors can enter contracts with guardian’s consent or assistance[11]. |

| India, United Kingdom | 18 | Most agreements by under-18s are unenforceable (exception for necessities), effectively barring unsupervised business dealings[13]. |

1.2.2 The Indispensable Role of Adults

To navigate these restrictions, underage entrepreneurs almost invariably require significant adult involvement:

- Legal Guardianship and Co-signing: Parents or guardians typically act as legal signatories for all business operations. This includes co-signing contracts, appearing as the registered owner of the business entity (e.g., an LLC), and opening business bank accounts, which minors cannot do independently[10].

- Trust Structures: For more substantial ventures or investments, a trust can be established where an adult trustee holds the business assets until the minor reaches the age of majority, ensuring the child is the beneficial owner[10].

- Corporate Roles: While a minor might be the visionary “CEO” of their startup, they often cannot legally hold certain formal corporate positions, such as a company director, in an incorporated entity without meeting age requirements (e.g., 18 in Malaysia)[46][47]. In such cases, parents or other adults serve as official directors, managing operational and legal responsibilities.

- Financing Access: Young entrepreneurs often face challenges accessing traditional finance. A significant 82% of youth-led companies report needing loans or external funding, yet banks are reluctant to lend to minors[45]. Adult co-signers or alternative funding methods (grants, crowdfunding, parental investment) become essential.

1.2.3 Patchwork Regulations and Evolving Legal Interpretations

The regulatory landscape is inconsistent, with some regions making strides to accommodate youthful enterprise:

- State-Level Variations: In the U.S., states like Colorado historically barred minors from forming companies, while others like Texas and California offer greater flexibility for teen entrepreneurs under adult supervision[14].

- Limited Legal Capacity: The Netherlands provides a pioneering model with “handlichting,” allowing 16-17 year-olds, via court petition, to gain limited legal capacity for business decisions, making them personally responsible for related obligations and reducing reliance on parental approval[12].

- “Lemonade Stand Laws”: A more informal adjustment, these laws (now in over a dozen U.S. states) exempt children’s small-scale, occasional businesses from permit requirements, acknowledging their role as educational experiences[30][31].

These varying approaches highlight a broader legislative challenge: balancing the protection of minors with increasing calls to foster early entrepreneurship. The growing presence of young founders pushes for legal innovation, perhaps moving towards a tiered system of contractual capacity that evolves with age and verified maturity, akin to other rights and responsibilities minors acquire. In the interim, diligence, clear legal structuring (often involving parents), and expert consultation remain critical for underage business owners and their families.

1.3 Balancing Business Endeavors with Child Labor Laws and Education

The rise of child and teen entrepreneurship introduces a compelling tension between established child labor laws, which are fundamentally designed to protect minors from exploitation, and the empowerment of young individuals to pursue their own ventures. Furthermore, the universal priority placed on education deeply impacts the operational realities of these youthful businesses.

1.3.1 Child Labor Laws in the Context of Self-Employment

Traditional child labor laws, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) in the U.S., set minimum working ages (often 14 for non-agricultural, non-hazardous work) and restrict working hours during school terms[48][49]. However, these laws were primarily formulated to regulate employment by external employers, not self-employment or work within a family business. This creates a nuanced area for kidpreneurs:

- Exemptions for Self-Employment and Family Businesses: Generally, self-employment and work in businesses wholly owned by parents are largely exempt from federal child labor restrictions, provided the work is not hazardous and does not interfere with schooling[50][52]. For instance, a 12-year-old can operate an online craft store or a landscaping service, or assist in a family-owned shop, activities that would typically be restricted if they were employed by an unrelated third party. This flexibility is intended to allow children to learn work skills in a supervised, safe environment.

- The “Employer” Dilemma: The primary concern for labor authorities often hinges on the employment relationship. If a minor’s business grows to a point where they hire other individuals, especially other minors, then the conventional child labor laws apply to those employees, and the young entrepreneur (or their adult proxy) assumes the responsibilities of an employer.

- Blurred Lines: Entrepreneurship vs. Exploitation: This distinction leads to ethical complexities. While a child running a small, self-directed venture is generally viewed positively, the line blurs if a child is coerced into an extensive, parent-driven business, especially if profits are not transparently allocated for the child’s benefit, or if the workload is excessive. This was highlighted by scandals involving family YouTube vloggers exploiting their children for revenue, leading to new protective legislation.

1.3.2 Educational Priority and Time Management

Education universally takes legal precedence over business activities for minors. Truancy laws and mandatory school attendance (up to 16 or 18 in many regions) restrict working hours during the school day or late into the night. Young entrepreneurs must demonstrate effective time management to balance academic responsibilities with their ventures. Mikaila Ulmer, founder of Me & the Bees Lemonade, famously maintained a 9 PM bedtime and operated her business only after homework and on weekends, highlighting a common strategy among successful kidpreneurs[53]. While some opt for homeschooling or online school for greater flexibility, these are not typical solutions for most. Policymakers and child advocates consistently stress that business pursuits should not compromise a minor’s academic performance or overall development.

1.3.3 Legal Relaxations for Micro-Enterprises: The “Lemonade Stand Laws”

In response to public outcry over instances where children’s informal businesses (like lemonade stands or bake sales) were shut down for lacking permits or violating health codes, a movement to simplify regulations for micro-enterprises has gained traction. Since 2017, at least 14 U.S. states have enacted “lemonade stand laws,” which exempt incidental, low-revenue youth businesses from permit and licensing requirements[30][31]. These legislative changes symbolize a recognition that fostering entrepreneurial spirit and teaching life skills at an early age outweighs the strict enforcement of regulations on such small-scale, educational ventures. Texas, for example, passed a “Bottle Bill” in 2019, while Illinois enacted the *Kid’s Lemonade Stand Act*, exempting unpermitted sales by minors under 16 up to a certain revenue threshold. These reforms illustrate a legislative willingness to differentiate between genuine learning experiences and more formal commercial undertakings, giving children a freer hand at the micro-business level.

1.3.4 Modern Protections for Child Entrepreneurs and Influencers

The digital age’s unique forms of child enterprise have spurred new regulatory responses targeting potential exploitation:

- France’s Influencer Law (2020): France pioneered legislation treating child influencers (under 16) as child performers, requiring government authorization for professional online content creation and mandating that a significant portion of their earnings be placed in a protected savings account until adulthood[26][27][54].

- U.S. State-Level Protections (2023-2024): Following suit, states like Illinois, California, Minnesota, and Utah passed laws compelling parents to save a percentage (often 15%) of income generated by featuring their children on social media. These laws also grant adult children the right to request the removal of past content and provide legal recourse for misused earnings[28][29][56].

These new regulations represent a critical evolution of child labor protections, extending them to the digital content creation economy and asserting accountability for adults benefiting from minors’ online activities. They aim to safeguard children’s financial future and agency, curbing exploitation while acknowledging the legitimacy of earning income through digital means.

In essence, navigating this domain requires vigilance from parents, clear guidance from mentors, and adaptable legislation. The objective is to cultivate the innovative spirit of young entrepreneurs without inadvertently subjecting them to excessive workloads, compromising their education, or exposing them to exploitation. The balance relies on a framework that enables responsible business exploration while prioritizing child welfare and development.

1.4 Digital Platforms: Enabling Ventures and Posing Compliance Challenges

The internet, social media, and digital platforms are double-edged swords for child and teen business owners. They have democratized access to markets and tools, enabling young entrepreneurs to reach global audiences from their bedrooms. However, this accessibility comes with a complex web of platform-specific policies and stringent regulatory requirements, particularly concerning age, data privacy, and content.

1.4.1 Age Restrictions on Online Platforms and Financial Services

A significant hurdle for young entrepreneurs operating online is the pervasive age restriction on most digital services critical for running a business:

- Payment Processors: Services like Stripe and PayPal generally require users to be at least 18 years old to create an account and process payments[15][17]. This means a teen selling products or services online must rely on a parent or guardian to set up and manage the payment gateway under their adult name.

- E-commerce Platforms: Marketplaces such as Etsy allow sellers aged 13-17, but only under the direct supervision of a parent or guardian, who must be the account holder and legally responsible for the shop[16][18]. Other platforms like Amazon or eBay also have similar age verification processes that necessitate adult proxy ownership for minors.

- App Stores and Developer Accounts: Even for aspiring app developers, while a minor can code an app, the legal entity or individual registering as a developer with platforms like Apple App Store or Google Play must typically be an adult.

These restrictions necessitate that young founders enlist adult allies not only for legal capacity but also for practical management of online transactions and financial liability. The business is formally registered under the adult’s name on these platforms, though the teen is often the creative force. This arrangement can lead to complications, especially concerning intellectual property ownership, if expectations are not clearly established between the minor and the adult proxy.

1.4.2 Social Media, Content Creation, and Monetization

For teen entrepreneurs who leverage content creation for marketing or as their primary business model (e.g., influencers, YouTubers), social media platforms introduce distinct rules:

- Minimum Age for Accounts: Major platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube generally require users to be at least 13 years old, primarily driven by U.S. COPPA regulations[21]. While many younger children circumvent these rules by misrepresenting their age, legally, they risk account termination.

- Monetization Limits: Even for teens aged 13-17, platform functionalities may be restricted. TikTok, for instance, prohibits live streaming or gifting for under-18 users. Crucially, monetization programs (e.g., YouTube Partner Program for ad revenue) demand the channel owner to be 18 or older, or that a legal guardian manages the payments. Similarly, brand deals or sponsorship contracts almost universally require an adult to sign on behalf of the minor.

This means that while teens can build massive audiences and influential brands online, the legal and financial mechanisms for monetizing their efforts require adult oversight. This “two-tier” system ensures that formal financial agreements and liabilities are managed by legally capable individuals.

1.4.3 Data Privacy Regulations: COPPA, GDPR, and Beyond

Young online entrepreneurs, particularly those whose businesses involve user data or cater to younger audiences, must comply with stringent data privacy laws:

- Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA): In the U.S., COPPA prohibits the collection of personal information from children under 13 without verifiable parental consent[19]. A teen developer creating an app or game, even unintentionally, that appeals to this age group must implement age-screening and parental consent mechanisms to avoid hefty fines from the FTC.

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Europe’s comprehensive data protection law includes specific provisions for minors, generally requiring parental consent for processing personal data of those under 16 (though member states can set this age between 13 and 16)[20]. This complex, international regulation means a teenage entrepreneur with global customers needs to understand and comply with varying age-of-consent requirements.

Ignoring these regulations, regardless of age, can lead to severe penalties. Therefore, young online business owners are well-advised to minimize data collection, utilize platform-provided compliance tools (e.g., YouTube’s “made for kids” designation), and seek adult guidance to understand their legal obligations. Proactive measures, such as developing privacy policies and terms of service, are essential.

1.4.4 Content Guidelines, Safety, and Financial Prudence

Beyond legal and privacy concerns, young online entrepreneurs must navigate platform content policies, online safety, and financial best practices:

- Community Guidelines: Adherence to platform-specific community guidelines is critical. This includes rules on advertising disclosures (e.g., for sponsored content) and appropriate content.

- Cybersecurity and Fraud: Minors, often less experienced in the nuances of online commerce, can be targets for scams. Implementing caution, using secure payment methods, and verifying partners are crucial.

- Taxes: A often-overlooked aspect is taxation. Regardless of age, if a minor earns income beyond a certain threshold, they are legally obligated to report it and pay taxes. This necessitates careful record-keeping and potentially consulting a tax professional.

The digital realm offers unparalleled opportunities for young entrepreneurs to innovate and thrive. However, it equally demands a high degree of digital literacy, legal awareness, and responsible adult oversight. Successful navigation requires young founders to treat their online ventures seriously, understanding that scaling success means adhering to a growing set of rules and responsibilities.

1.5 Ethical and Safety Considerations: Safeguarding Young Entrepreneurs

The increasing visibility and success of child and teen entrepreneurs bring forth a host of ethical and safety considerations, primarily focused on balancing the developmental needs and well-being of young individuals with the demands and potential pitfalls of running a business. This section examines the delicate balance between fostering youthful initiative and protecting minors from exploitation, undue pressure, and potential harm.

1.5.1 Parental Involvement: Support vs. Exploitation

Parents and guardians are almost universally involved in the ventures of underage entrepreneurs, serving roles ranging from legal representatives and financial managers to mentors and emotional support. In the most beneficial scenarios, this involvement fosters valuable life skills (financial literacy, problem-solving, resilience) and ensures that profits are managed prudently, typically for the child’s future education or business reinvestment. Mikaila Ulmer’s parents, for instance, helped with logistics but allowed her creative leadership, ensuring profits benefited her and bee conservation efforts[57][59]. Similarly, Moziah Bridges’ mother handled the legal paperwork, allowing him to focus on design and brand development, including securing a significant NBA licensing deal[61].

However, the ethical line can be crossed if parental involvement devolves into exploitation. Cases of “stage parents” pushing children into ventures they don’t enjoy or siphoning off profits for personal gain are a serious concern. The lack of legal capacity for minors makes them particularly vulnerable, as they often cannot easily sue their parents or understand their financial rights. This vulnerability has spurred protective legislation, such as California’s Coogan Law (and its modern extensions to social media influencers), which mandates that a portion of a child’s earnings be placed in court-monitored trust accounts until they reach adulthood[63]. Ethically, it is widely accepted that a child’s business earnings, after reasonable expenses, belong to the child, and parents should act as fiduciaries rather than outright owners. Transparency in financial management, even as simple as reviewing ledgers with the teen, can build trust and critical financial literacy.

1.5.2 Financial Literacy and Fair Dealings

Operating a business exposes young people to complex financial concepts such as pricing strategies, cost analysis, investment, and equity negotiation. Without proper guidance, minors are susceptible to making ill-informed decisions, such as taking on excessive debt or undervalue their intellectual property. The story of Nick D’Aloisio, who sold his Summly app to Yahoo for $30 million at 17, underscores the importance of experienced legal counsel. His parents and lawyers were heavily involved in the negotiation, ensuring trust accounts held a portion of the payout until he came of age and that Yahoo was comfortable with the legality of the contracts[65][67]. Such high-stakes transactions necessitate independent legal advice to protect the minor’s interests. Some jurisdictions even require court approval for contracts involving minors above a certain financial threshold, especially in the entertainment industry, which arguably should extend to significant entrepreneurial deals. Beyond specific transactions, teaching comprehensive financial literacy (beyond merely making money) is an ethical imperative for any adult guiding a young entrepreneur.

1.5.3 Health, Well-being, and Avoiding Burnout

Entrepreneurship is inherently demanding, and for children and teenagers, balancing business responsibilities with academic life, social development, and personal well-being can be overwhelming. There is a tangible risk of burnout, particularly if a venture achieves rapid success and the young founder feels compelled to meet adult-level expectations. The pressure of public visibility can also lead to stress, bullying from peers, or unwanted media attention. Experts and parents alike emphasize that a child’s holistic development and mental health must take precedence over business success[25]. This includes ensuring adequate sleep, maintaining strong social connections, and participating in age-appropriate leisure activities. Parents and mentors should actively monitor for signs of stress and be prepared to scale back the business or bring in additional adult support (e.g., hiring a manager) if the workload becomes detrimental to the child. The ethical stance is clear: no amount of business success justifies compromising a child’s physical or mental health.

1.5.4 Professional Conduct and Online Safety

Young entrepreneurs frequently interact with adults as customers, suppliers, investors, or collaborators. A unique challenge arises from being taken seriously while simultaneously navigating the inherent power imbalance. While many adults are supportive, there are unfortunately cases of predatory behavior. Therefore, safety protocols are critical for minors: always involving a trusted adult in communications, and never agreeing to private meetings without supervision in public spaces. Building a network of supportive peers through organizations like DECA or NFTE can provide a crucial sounding board and peer support. Online interactions also carry risks, from scams to inappropriate solicitations. Minors need to be educated on digital safety, responsible online conduct, and the importance of maintaining professional boundaries. The digital exposure of operating an online business can amplify these risks, underscoring the need for continuous vigilance and adult guidance.

1.5.5 Regulatory Ethics: Fostering a Fair Ecosystem

On a broader societal level, the rise of child entrepreneurs compels a discussion about the ethical responsibility of regulators and the business ecosystem. Should there be special support mechanisms (e.g., grants, tax breaks tailored for under-18s) to encourage youth entrepreneurship? While fostering innovation is valuable, it must be balanced with preventing mechanisms that could allow parents to circumvent labor laws or transfer liabilities. The new influencer laws, which compel funds to be placed into child-specific accounts, aim to create a fairer playing field by direct legislative intervention. The ongoing ethical debate centers on how to create an environment that truly empowers young people to innovate and learn, rather than inadvertently creating pathways for their exploitation. Ultimately, the ethical bedrock of child and teen entrepreneurship must prioritize the child’s welfare and long-term development above short-term profits or business achievements. When responsibly managed, youth ventures can be transformative learning experiences, instilling confidence and valuable skills that extend far beyond the balance sheet.

Notable Examples: Illustrating the Landscape

The narratives of successful child and teen entrepreneurs vividly demonstrate the opportunities, legal complexities, and critical need for adult guidance and support within this emerging landscape. These case studies highlight how young visionaries, with the right framework, can achieve extraordinary success.

Mikaila Ulmer – BeeSweet/Me & the Bees Lemonade (USA)

Mikaila Ulmer started her lemonade business at the remarkable age of four in Austin, Texas, inspired by a mission to save honeybees with her great-grandmother’s recipe. With parental assistance, her early sales at local fairs gained traction. Her national breakthrough occurred at age nine in 2015 when she secured a $60,000 investment from Daymond John on the television show *Shark Tank*[14]. By age 11, Mikaila’s product, rebranded as “Me & the Bees Lemonade,” was distributed in over 55 Whole Foods Market stores, a deal reportedly worth millions[59]. By 2018, it was in over 500 stores, and she had authored a children’s book. Her parents were instrumental, managing contracts (including a low-interest loan from Whole Foods) and establishing a proper business entity with Mikaila as the founder and CEO while providing adult oversight[59]. Profits also funded bee conservation, aligning with her social mission. Mikaila’s unwavering commitment to education, even amid business success, showcases how responsible parental guidance and a strong purpose can scale a child-led startup into a sustainable enterprise, navigating complex partnerships and finances.

Moziah “Mo” Bridges – Mo’s Bows (USA)

Moziah Bridges initiated Mo’s Bows at nine, hand-sewing bow ties in Memphis. Seeking stylish children’s accessories, he created his own and started selling them, with his mother managing the necessary business paperwork. At 12, Mo appeared on *Shark Tank* in 2014, where he famously accepted Daymond John’s offer of ongoing mentorship without an equity deal—a testament to wise guidance and a long-term vision. Under John’s mentorship, Mo’s Bows gained significant recognition. In 2017, at just 15 years old, Moziah inked a landmark licensing deal with the NBA to design bow ties representing all 30 professional basketball teams[61]. Valued in the seven figures, this deal was unprecedented for such a young entrepreneur. His mother, Tramica, formally served as CEO and signed the critical NBA contract, maintaining a family-run business structure with Mo as the creative director[61]. This partnership prioritized gradual growth and brand building over immediate financial gain. Mo’s story exemplifies how strong mentorship is crucial for youth navigating major corporate deals, ensuring legal and financial responsibilities are handled appropriately while the young founder focuses on their passion.

Nick D’Aloisio – Summly app (UK)

Nick D’Aloisio taught himself coding in London and at 15 developed “Summly,” a mobile app that used AI to summarize news articles. The app’s innovative approach quickly garnered attention, leading D’Aloisio to secure approximately $1.5 million in venture capital while still in high school. In March 2013, at only 17, D’Aloisio sold Summly to Yahoo for an estimated $30 million, a deal primarily structured as a cash and stock transaction[65]. Following the acquisition, he joined Yahoo’s London office as a product manager before his 18th birthday. Given his minor status, his parents and legal team were extensively involved in the acquisition negotiations, and trust accounts were established for a portion of the payout until he reached adulthood[65]. The Yahoo deal essentially involved acquiring his incorporated company (which required adult oversight) and subsequently employing D’Aloisio. His experience highlights the potential for extraordinary success in the tech sector for young entrepreneurs, but it also underscores the absolute necessity of robust legal support to manage complex transactions when the founder is still a minor. D’Aloisio’s story sparked public debate on minors owning valuable intellectual property (Time magazine provocatively titled an article: “Why Is That 17-Year-Old’s $30 Million App Even Legal?”)[67].

Tilak Mehta – Papers N Parcels (India)

Tilak Mehta, from Mumbai, presented a non-Western example of precocious entrepreneurship. At 13 years old in 2018, he founded “Papers N Parcels,” a courier service offering same-day delivery within the city. Drawing inspiration from Mumbai’s traditional dabbawalas, he partnered with a logistics veteran who took on the CEO role while Tilak provided the vision. Within a year, the company had expanded to employ hundreds of delivery personnel (including dabbawalas) and received significant media coverage. By 2021, at the age of 16, Papers N Parcels reportedly achieved a turnover exceeding ₹100 crore (approximately $13 million), with Tilak’s stake valued at about ₹65 crore (~$8 million)[68]. Due to his minor status, Tilak could not legally serve as a company director or sign contracts in India; thus, his business was formally registered with adult directors (his family and partner). His father played a crucial role in initial funding and ensuring compliance. Despite initial skepticism from clients regarding a 13-year-old founder, the company transparently communicated that experienced adults managed daily operations, with Tilak contributing ideas and promotional efforts. Tilak’s success demonstrates that even in traditional industries like logistics, young innovators can thrive with a blend of youthful vision and experienced adult management, urging local discussions on encouraging student entrepreneurship for problem-solving within ethical and legal frameworks.

These examples illustrate the growing capacity of minors to build successful businesses across diverse industries and geographies. They collectively underscore the indispensable role of supportive, ethical adult guidance within appropriate legal structures to navigate the complexities posed by age-of-majority laws, financial regulations, and the unique challenges of public visibility. The journey for these young founders is not just about profit, but also an accelerated education in business acumen, resilience, and the intricate dance between ambition and compliance.

2. The Rise of Youth Entrepreneurship in the Digital Age

The entrepreneurial landscape is undergoing a significant transformation, with young people increasingly at its forefront. Fueled by advancements in digital technology, a shifting cultural mindset, and a desire for autonomy and impact, a new generation of “kidpreneurs” and “teen CEOs” is emerging. This phenomenon represents a departure from traditional career paths and reflects a proactive engagement with economic opportunities, often at ages previously considered too young for serious business endeavors. This section delves into the dramatic ascent of youth entrepreneurship, examining the statistical evidence, global trends, and the underlying drivers that propel young individuals into the world of business ownership in the digital age.

2.1 A Surge in Entrepreneurial Aspirations Among Youth

The past few years have witnessed a remarkable uptick in entrepreneurial ambition among young people, particularly teenagers. Data from various surveys paints a clear picture of this accelerating trend. In 2018, only 41% of teenagers reported being open to the idea of starting their own business[1]. By 2022, this figure had soared to a striking 75%[2], indicating a near doubling of interest in just four years. This substantial increase highlights a fundamental shift in career perceptions among youth. Generation Z, broadly defined as those born between the mid-1990s and early 2010s, is frequently characterized as the most entrepreneurial generation to date[3]. A 2021 survey revealed that over half (53%) of young people in this demographic plan to launch their own venture within the next decade[5]. For the segment of Gen Z already in the workforce, this ambition was even higher, with 65% intending to start a business within a similar timeframe[5]. This demonstrates that as young individuals gain real-world experience, their entrepreneurial intent tends to solidify, recognizing opportunities to carve their own paths.

| Category | 2018 Data | 2022 Data | Trend/Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teens Considering Entrepreneurship | 41%[1] | 75%[2] | Significant increase in entrepreneurial ambition (nearly doubled). |

| Teens Who Have Already Started a Business (by high school age) | ~5%[6] (6% of boys, 4% of girls) | (Data not updated, but generally remains a minority) | Large gap between aspiration and current active participation, though early starts are notable. |

Despite the burgeoning interest, the actual number of minors actively operating businesses remains a distinct minority, particularly in advanced economies. In the U.S., for instance, only about 5% of teenagers had already initiated an entrepreneurial venture by high school age as of 2018[6]. This figure, though relatively small, signifies a tangible increase in the visibility of young founders. Globally, the landscape is more varied. An estimated one in four young people (ages 15–24) worldwide are self-employed or running a small business, though this is largely driven by necessity in developing regions where formal employment opportunities are scarce[3]. In contrast, advanced economies like the European Union saw a much lower rate of youth self-employment, with only about 6.5% of employed youth (20–29 years old) being self-employed in 2018, less than half the overall adult self-employment rate of 13.5%[4]. Moreover, the number of self-employed youth in the EU actually decreased from 2.7 million in 2009 to 2.5 million in 2018[4], suggesting differing regional dynamics and drivers. The current generation of young entrepreneurs is not solely motivated by financial gain. There is a strong undercurrent of social consciousness driving many of these ventures. A significant 58% of teenagers surveyed in 2022 expressed a willingness to start a business focused on addressing a societal or environmental need, even if it meant potentially earning less money[2]. This highlights a generational preference for purpose-driven enterprise, where impact is as important as profit. This intrinsic motivation to “start young to make a difference” is further supported by the sentiment that nearly 80% of teens believe the ideal age to launch a business is before 30[2].

2.2 Digital Platforms: Lowering Barriers and Raising Challenges

The proliferation of digital technologies has irrevocably altered the entry barriers to entrepreneurship for young people. The internet and social media have effectively democratized access to markets, customers, and even funding, enabling enterprising children and teenagers to establish ventures from their homes that can reach a global audience. Whether it is an Etsy shop selling handmade crafts, a monetized YouTube channel, a dropshipping business, or a sophisticated app startup, digital natives possess the tools to transform ideas into viable businesses. This accessibility is a primary driver behind the surge in youth entrepreneurial interest.

2.2.1 Platform Age Restrictions and Parental Involvement

While digital platforms provide unprecedented opportunities, they also introduce a complex layer of age-related restrictions. Most major online services crucial for business operations—including payment processors like Stripe and PayPal, e-commerce sites such as Etsy, and platforms like YouTube that facilitate content monetization—mandate users to be at least 18 years old or require direct parental supervision or account ownership. For instance, Stripe necessitates a legal guardian’s sign-off for any account operated by an individual under 18[10]. Similarly, Etsy permits teenagers aged 13 to 17 to sell goods, but only under the direct supervision of a parent or guardian who holds the account[11]. This reality means that while a young founder might be the creative and operational force behind their online business, an adult ally is almost always required to navigate critical aspects such as payment processing, contractual obligations, and legal liability. This reliance on adult intermediaries can sometimes complicate the perceived ownership structure. The business might be formally registered under a parent’s name on a platform, even if the creative vision and daily operations are entirely the child’s. Clear communication and documentation within families are crucial to ensure that the youth’s ownership of the intellectual property and overall venture is recognized and protected, safeguarding against potential disputes should relationships sour.

2.2.2 Data Privacy and Content Regulations

Young entrepreneurs operating in the digital sphere must also contend with a specific set of regulations designed to protect minors online, primarily related to data collection and content. Laws such as the U.S. Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) and Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) are highly relevant. COPPA, for example, strictly regulates the collection of personal information from children under 13, requiring verifiable parental consent[14]. This means a 17-year-old app developer creating a game for younger children must implement age screening mechanisms and parental consent protocols. Failure to comply can lead to significant penalties, underscoring that these laws apply irrespective of the business owner’s age. Similarly, GDPR imposes strict requirements for processing personal data of children, typically setting the age of consent between 13 and 16, depending on the member state[15]. A teen operating a global website could unintentionally violate GDPR if they collect data from a 15-year-old in a region where the age of consent for data processing is 16. The complexity of these international regulations poses a significant challenge for young, often unadvised, entrepreneurs. Beyond data privacy, social media and video platforms enforce their own content and conduct guidelines. Most major social media platforms bar users under 13, a measure often stemming from COPPA guidelines[16]. Teenagers aged 13-17 often face reduced functionality; for example, TikTok limits live streaming and gifting for under-18 users, and YouTube disables personalized advertising on content designated as “made for kids.” The monetization of content for minors also necessitates adult involvement, with platforms like YouTube requiring channel owners to be 18 or have a guardian handle payments through the YouTube Partner Program. This creates a fascinating paradox: a minor might create hugely popular content or a successful digital product, yet legally be too young to fully contract with the platforms that facilitate their business. This regulatory gray area highlights the evolving challenges in governing online youth enterprise.

2.3 Global Trends and Underlying Drivers

Youth entrepreneurship is a global phenomenon, though its manifestations and drivers vary considerably across different economic contexts.

2.3.1 Divergent Paths in Developed vs. Developing Economies

While 25% of young people globally (15-24 years old) are self-employed or entrepreneurs[3], this aggregation masks important regional distinctions. In many developing nations across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, youth entrepreneurship is often a necessity-driven response to high youth unemployment and limited formal job markets. Young individuals, faced with a lack of conventional employment, turn to micro-enterprises in sectors like retail, agriculture, or handicrafts to create their own livelihoods. Conversely, in high-income countries, youth startups are typically opportunity-driven, fueled by innovation, personal interest, and leveraging digital tools. Examples include teenage app developers, online fashion boutiques, or specialized craft shops on platforms like Etsy. The motivation here is often to pursue a passion, develop skills, or address a perceived market gap, rather than mere survival. Nonetheless, a unifying factor worldwide is the transformative power of the internet and mobile technology, which enables young entrepreneurs, even in rural areas of emerging economies, to connect with broader markets.

2.3.2 The Shifting Mindset: DIY Ethic and Social Impact

Several factors contribute to the “why now?” inquiry regarding the rise of youth entrepreneurship:

- Technological Accessibility: The ease with which a teenager can build a brand, develop a product, and market it globally using a smartphone and internet access has dismantled many traditional barriers to entry.

- DIY Ethic: Gen Z exhibits a strong “Do It Yourself” ethos, comfortable with self-directed learning and leveraging online resources (e.g., YouTube tutorials) to acquire new skills. This fosters confidence in initiating independent projects[35], [36].

- Influence of Digital Role Models: The highly visible success stories of young influencers and startup founders in the digital space make entrepreneurship seem more attainable and glamorous, often contrasting with the perceived drudgery of cubicle jobs.

- Autonomy and Purpose: This generation values autonomy, flexibility, and the ability to contribute to meaningful causes. Entrepreneurship offers a direct path to personal agency and impactful work, aligning with the “yearn for careers that enable original thought and ideas”[37] noted by Junior Achievement’s CEO.

- Decline of Traditional Youth Jobs: As traditional entry-level jobs like paper routes or retail positions have diminished in some regions, creating one’s own opportunities has become a practical alternative.

2.4 Challenges and Obstacles: The Gap Between Aspiration and Reality

Despite the enthusiasm, young aspiring entrepreneurs face significant hurdles, preventing many from translating their ambition into actual business ventures.

2.4.1 Fear of Failure and Knowledge Gaps

A primary deterrent for young entrepreneurs is the apprehension of failure. A 2018 survey indicated that 67% of teens (aged 13-17) cited the possibility of business failure as a reason that might prevent them from pursuing entrepreneurship[8]. This fear is a universal entrepreneurial challenge but can be particularly paralyzing for young individuals who may lack the experience and resilience that come with age. Furthermore, many young people feel ill-equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills. In 2022, over half (55%) of teenagers reported needing more information on how to succeed as an entrepreneur[9]. The absence of practical guidance and mentorship is also acutely felt, with 32% of teens stating that a business-owner mentor or role model would be crucial for their entrepreneurial journey[9]. This highlights the critical role of support systems:

- Education: Schools and non-profit organizations (e.g., Junior Achievement with programs like “JA Launch Lesson”) are increasingly integrating entrepreneurship curriculum, incubators, and networking events tailored to youth[10], [11].

- Mentorship: Connecting young founders with experienced entrepreneurs can provide invaluable guidance, build confidence, and help demystify the complexities of business.

- Low-Stakes Opportunities: Providing environments for experimentation, such as school business projects or supervised pop-up markets, can help alleviate the fear of failure and build practical skills.

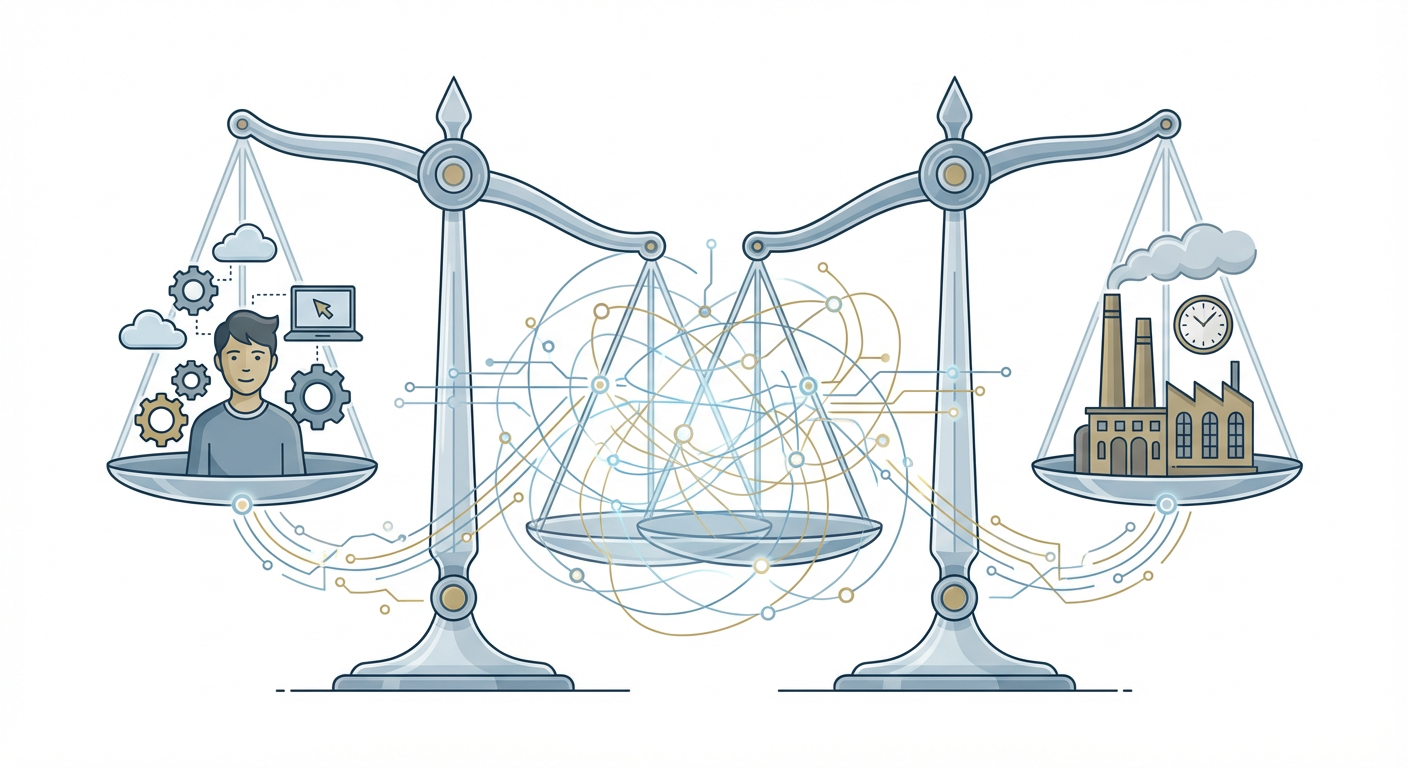

2.4.2 Legal Barriers: Contractual Capacity and Business Formalities

The most significant systemic barrier to youth entrepreneurship lies in legal frameworks. Most jurisdictions globally establish 18 as the age of majority, the legal threshold at which an individual can enter into binding contracts, assume legal obligations, and form corporate entities without adult intervention[7], [74]. This is primarily a protective measure, shielding minors from being exploited or entering into agreements they may not fully understand. The consequence for aspiring young business owners is profound:

- Contractual Incapacity: A contract signed by a minor is typically voidable at the minor’s discretion[74]. While this protects the minor, it makes other parties hesitant to enter into agreements directly with them, as the contract might not be enforceable.

- Entity Formation: Minors generally cannot independently incorporate companies or act as primary directors or officers without adult involvement[8], [75].

- Financial Access: Underage individuals often face immense difficulty opening business bank accounts or securing loans, as financial institutions require adult guarantors or official account holders[11]. This “catch-22” forces young founders to rely on personal savings, parental support, or alternative funding mechanisms like grants and crowdfunding.

The legal landscape for minor entrepreneurs is a patchwork of rules:

- Standard Adult Involvement: The most common solution involves a parent or guardian acting as the legal signatory for the business – co-signing contracts, serving as directors, or opening accounts on behalf of the child. The child remains the beneficial owner, with informal or formal agreements for future ownership transfer[30].

- Regional Variations: Regulations for minors in business vary widely.

- In the [9]”>Netherlands, 16- and 17-year-olds can petition a court for “limited legal capacity” (handlichting), granting them the ability to make specified business decisions independently[10].

- [5]”>South African law allows minors as young as 7 to enter contracts, provided they have parental or guardian consent[12].

- Contrastingly, countries like [5]”>India and the UK treat most agreements by under-18s as unenforceable (exceptions typically for necessities), significantly restricting unsupervised business dealings[12].

- Within the [7]”>U.S., some states (e.g., Colorado) historically prohibited minors from forming companies, while others (e.g., Texas, California) offer more flexibility with adult supervision[13].

- Corporate Roles: While a minor can undoubtedly function as a “CEO” in practice, holding formal corporate positions like a company director on the board (e.g., in the UK) or being an incorporator is often restricted until age 18. Shares can sometimes be held in custodial accounts for a minor, with adults managing the entity.

These complexities mean that navigating the legal maze often requires professional advice and continuous parental involvement to structure the business legitimately and protect all parties.

2.5 Evolving Regulations: Adapting to the New Reality

Governments and regulatory bodies are beginning to acknowledge the rise of youth entrepreneurship and are slowly adapting legal frameworks, albeit often prompted by public outcry or specific incidents.

2.5.1 Child Labor Laws and Exceptions

Traditional child labor laws are designed to protect youth from exploitation in employment settings, setting minimum working ages (e.g., 14 for non-hazardous work in the U.S. FLSA), limiting work hours during school semesters, and prohibiting dangerous occupations[14]. However, these laws typically target relationships where a minor is *employed by another party*. They generally include exemptions for:

- Self-employment: Children working for themselves on small-scale ventures (e.g., an online crafts shop, lawn care) are largely unregulated by child labor laws, provided it does not interfere with schooling or safety[15].

- Family businesses: Minors can often work in businesses wholly owned by their parents at younger ages and for longer hours than in external employment, with exceptions for hazardous work[15].

This distinction means a 12-year-old running their own micro-enterprise generally operates within legal boundaries, whereas that same child couldn’t be hired as an employee by an unrelated company. The intent is to foster skill development and allow involvement in family enterprises without enabling exploitation.

2.5.2 “Lemonade Stand” Laws

A symbolic victory for young entrepreneurs has been the widespread adoption of “lemonade stand laws.” After numerous instances where children’s informal stands were shut down for lacking permits or violating health codes, public backlash led to legislative changes. Since 2017, over a dozen U.S. states have passed laws exempting children’s occasional, small-scale businesses from permit and licensing requirements[16]. Utah’s 2017 law, for example, prevents local authorities from requiring licenses or fees for businesses operated by minors on a limited basis[17]. These laws, enacted in states like Utah, Colorado, and Texas, recognize these ventures as valuable learning experiences rather than formal commercial enterprises, effectively creating carve-outs for low-revenue youth businesses.

2.5.3 Protections for Child Influencers

The digital age has introduced a new category of child entrepreneur: the “child influencer” or content creator. The lucrative nature of online content, coupled with instances of parental exploitation, has spurred new regulations.

- In 2020, [18]”>France passed a pioneering law regulating “kid influencers” under 16, treating them as child performers under labor law. This legislation mandates prior government approval for their online activities and requires a significant portion of their earnings to be set aside in a protected account until they turn 18[19], [20].

- Inspired by similar concerns, at least [11]”>four U.S. states (Illinois, California, Minnesota, Utah) enacted laws by 2024 compelling parents to save a percentage (typically 15%) of income generated by featuring their children on social media[21], [22]. These laws also grant former child influencers the right to request the deletion of videos once they reach adulthood and provide legal recourse for misused earnings.

These developments represent a crucial extension of child protection laws into the rapidly evolving digital economy, signaling a systemic effort to balance entrepreneurial opportunity with safeguarding children’s welfare.

2.6 Ethical Implications and Well-being Safeguards

The growing visibility of youth entrepreneurs has brought to the forefront critical ethical considerations surrounding exploitation, undue pressure, and the overall well-being of young business owners.

2.6.1 The Line Between Support and Exploitation

While many advocate for “kidpreneurs” as a positive developmental opportunity, critics warn against the potential for hidden child labor or parental overreach. Parents play an indispensable role in youth ventures, often serving as legal representatives, mentors, and financial managers. The ethical dilemma arises when parental involvement shifts from supportive guidance to coercive control or exploitation. High-profile scandals involving family YouTube vloggers misusing their children for revenue underscore the need for robust safeguards[12]. These incidents necessitate clear distinctions where the child’s earnings are protected (as exemplified by the new influencer laws), and parental actions prioritize the child’s best interests as fiduciaries, not owners, of the business. Transparency in finances and teaching financial literacy are key to fostering trust and responsible management.

2.6.2 Burnout and Balancing Childhood Development

Entrepreneurship, a demanding pursuit for adults, can be particularly challenging for children and teenagers who are simultaneously navigating academic pressures, social development, and physical growth. There is an inherent risk of burnout if business demands overshadow schooling, downtime, and normal childhood experiences. Experts consistently emphasize that minors should not sacrifice their education or holistic development for business success[13]. Inspiring young entrepreneurs like Mikaila Ulmer of “Me & the Bees Lemonade” famously balanced her booming business with her schoolwork, stating, “I work on the business after I do my homework”[14]. Maintaining a healthy balance requires:

- Time Management: Integrating business activities around school schedules, extracurriculars, and personal time.

- Parental Oversight: Parents and mentors must be vigilant for signs of stress, ensuring adequate rest, social engagement, and academic performance.

- Scope Management: Occasionally, it may be necessary to scale down the business or delegate responsibilities to adults if the workload becomes overwhelming for the young founder.

The ethical imperative here is clear: the child’s well-being and healthy development must always take precedence over business profits or rapid growth.

2.6.3 Need for Mentorship and Educational Support

The significant knowledge and mentorship gaps identified by surveys reinforce the need for comprehensive support systems. Young entrepreneurs require not just capital, but human capital—experienced guidance to overcome challenges. Educational institutions, non-profits, and even corporations are increasingly stepping in to provide this support through:

- Entrepreneurship courses and specialized programs.

- Business incubators and pitch competitions for youth.

- Mentoring networks connecting young founders with seasoned professionals.

- Innovation challenges and funding opportunities specifically for under-18 ventures.

The consensus among educators and policymakers is that with the right combination of educational resources, mentorship, and parental guidance, young innovators can successfully navigate both the entrepreneurial journey and its associated regulatory complexities.

2.7 Conclusion

The rise of youth entrepreneurship in the digital age is a powerful trend, driven by technological accessibility, a generational shift towards purpose-driven work, and a natural inclination for autonomy. While the entrepreneurial ambition among young people is at an all-time high, translating this interest into actual ventures is often complicated by a web of legal restrictions, knowledge gaps, and ethical considerations. The evolving regulatory landscape, marked by reforms like “lemonade stand laws” and protections for child influencers, indicates a growing recognition of the unique challenges and opportunities presented by this demographic. As more young minds leverage digital tools to innovate and create, the onus is on society to provide the necessary support—legal clarity, educational resources, and ethical safeguards—to nurture this burgeoning entrepreneurial spirit responsibly. The next section will delve deeper into the legal framework surrounding minors’ contractual capacity, exploring the historical basis for these restrictions and examining how different jurisdictions attempt to balance protection with empowerment.

3. Legal Capacities and Contractual Limitations for Minors

The burgeoning interest in youth entrepreneurship, often fueled by the accessibility of digital platforms and a generational inclination towards self-driven ventures, presents a complex legal and ethical landscape. While the digital age has significantly lowered barriers to entry for aspiring young business owners – enabling teens to launch e-commerce stores, develop apps, or manage social media channels from their bedrooms – the fundamental legal structures governing minors remain largely rooted in traditional principles designed to protect children, not empower them as CEOs. This section delves into the intricate legal capacities and contractual limitations that minors encounter when pursuing business activities, highlighting the critical need for adult involvement in critical processes such as business registration, contractual agreements, and financial management across various jurisdictions. Drawing on specific data points, legal precedents, and real-world examples, we will explore the disparities in regulatory frameworks globally, the evolution of certain laws to accommodate youth enterprise, and the ongoing tension between safeguarding minors and fostering their entrepreneurial spirit.

3.1. The Age of Majority: A Foundational Barrier to Business Autonomy

At the heart of the legal challenges faced by child and teen business owners is the prevailing concept of the “age of majority.” This legal designation marks the transition from childhood to adulthood, granting individuals full legal rights and responsibilities. In most jurisdictions worldwide, including the vast majority of the United States, the age of majority for engaging in binding business activities and forming legal contracts is 18 years old9. This internationally recognized threshold is primarily intended to protect minors from exploitation, harmful decisions, and contractual obligations that they may not fully comprehend due to their age and presumed lack of maturity and business experience. The implications of this legal standard are profound for young entrepreneurs. While an enterprising 15-year-old might possess an innovative product idea, a strong business plan, and even a burgeoning customer base, their legal status as a minor significantly curtails their ability to operate independently in the formal business world. They generally cannot:

- Form Binding Contracts: Agreements signed by someone under 18 can often be voided or disaffirmed by the minor, even if the other party understood they were dealing with a minor5. This means a minor cannot reliably enter into agreements with suppliers, landlords, customers, investors, or engage in any other transaction that requires a legally enforceable contract7. The ability of a minor to avoid a contract is a safeguard but also a deterrent for businesses reluctant to deal with them directly.

- Register a Business Entity: Most governmental bodies responsible for business registration (e.g., for an LLC or corporation) require the principal individuals (organizers, directors, managing members) to be of legal age. This often restricts minors from formally incorporating a company or holding significant corporate roles9.

- Open Business Bank Accounts or Obtain Loans: Financial institutions typically require account holders to be at least 18 years old to open an account or independently apply for credit. This makes it challenging for minors to manage business finances, receive payments, or secure necessary funding without adult intervention12. Indeed, surveys indicate that 82% of youth-led companies need external funding, yet youth-led firms are less likely to even have a business bank account12.

These limitations mean that despite the growing entrepreneurial ambition among youth—with 75% of teenagers in 2022 expressing interest in starting a business, a sharp increase from 41% in 201812—only a small fraction, approximately 5% of U.S. teens by high school age, have actually launched a venture1. This gap highlights the significant legal barriers that transform aspiring “kidpreneurs” into fully operational business owners. The requirement for adult involvement isn’t merely a bureaucratic hurdle; it stems from a legal philosophy that minors, by definition, may lack the judgment and experience to fully understand the consequences of their commercial actions. This protective stance, while well-intentioned, often forces young innovators to navigate a labyrinth of adult proxies and legal structures, as demonstrated by the case of Mikaila Ulmer, who started her lemonade business at 4. At age 9, she secured a $60,000 investment on *Shark Tank*, and by 11, her “Me & the Bees Lemonade” was distributed in over 55 Whole Foods stores1415. Throughout this incredible growth, her parents were indispensable, managing contracts and loans, and setting up the formal business entity with appropriate adult oversight14. Similarly, Moziah “Mo” Bridges, who founded Mo’s Bows at age 9, leveraged the constant legal and operational support of his mother, who served as the de facto CEO and signatory for major deals, including a seven-figure licensing agreement with the NBA when Mo was 15 years old1316. Such real-world success stories consistently underscore that while a minor can be the creative force and public face of a business, an adult’s legal capacity is almost always essential for formal operations.

3.2. Patchwork of Regulations: Jurisdictional Variations and Limited Legal Capacities

The legal landscape governing minors in business is not uniform; instead, it presents a “patchwork of rules” that vary significantly across different jurisdictions. This global disparity offers unique challenges and opportunities for young entrepreneurs, as some regions provide more flexibility than others.

3.2.1. Global Variations in Legal Capacity

While 18 is the standard age of majority in many countries, exceptions and specialized pathways exist.

- South Africa: South African law offers a notable degree of flexibility, allowing children as young as 7 to enter into contracts, provided they have a guardian’s assistance or consent at the time of the agreement5. This means that a contract entered by a minor with guardian approval is not automatically voidable, a significant departure from many other common law systems.

- Netherlands: The Netherlands provides a specific mechanism for 16–17-year-olds to gain “limited legal capacity” (known as “handlichting”) by petitioning a court6. If granted, this status allows the minor to make certain business decisions independently, free from parental approval, and holds them personally responsible for their business obligations until they reach full adulthood at 186. This legal recognition of increasing maturity for specific purposes offers a valuable pathway for older teens seeking more autonomy.

- India and the UK: In contrast, countries like India and the United Kingdom adhere to stricter interpretations of contractual capacity for minors. Many agreements entered by individuals under 18 are generally considered unenforceable, except for contracts pertaining to “necessities” (such as food, clothing, or essential services). This effectively bars unsupervised business dealings and places a greater onus on adult involvement. Legal scholar Shivangi Gangwar’s analysis highlights the comparative differences in how these countries handle minors’ contracts in the digital age, underscoring the enduring protective stance in India and the UK5.

3.2.2. U.S. State-Level Discrepancies

Even within a single country like the United States, the rules can differ significantly from state to state.

- Restrictive States: Some states, such as Colorado and Illinois, have historically maintained strict policies that effectively prevent individuals under 18 from formally incorporating a company or holding directorships10. This can create substantial hurdles for young entrepreneurs in these regions, necessitating more elaborate adult-led structures.

- More Flexible States: Other states, however, offer greater flexibility. For example, Texas and California provide more leeway, allowing minors to engage in business activities with parental consent or, in certain circumstances, through court petitions for emancipation710. While emancipation is a relatively rare and rigorous process, usually tied to self-sufficiency rather than purely entrepreneurial aims, it signifies a legal pathway to full contractual capacity.

These varying regulations mean that the feasibility of a teen formally registering and operating a business can be heavily dependent on their geographic location. This lack of uniformity complicates the journey for young entrepreneurs and emphasizes the need for localized legal advice.

3.2.3. Parental Consent and Guardianship Structures: The Primary Workaround

Given the prevalent age restrictions and contractual limitations, the most common and practical solution for minors striving to run a business involves significant parental or guardian involvement. These adults act as legal proxies, providing the necessary contractual capacity and formal structure.

- Co-signing and Formal Roles: Parents or guardians often must co-sign contracts, serve as managing members for LLCs, or act as directors for corporations on behalf of the minor7. For example, a 16-year-old wishing to establish an LLC typically needs an adult to be listed as the organizer or a designated managing member with legal authority7.

- Business Registration and Banking: The adult typically registers the business entity in their own name, or as a co-owner, and opens business bank accounts, as minors generally cannot do so independently. Mikaila Ulmer’s father, for instance, accompanied her to meetings and managed contracts and loans with Whole Foods, reflecting this critical adult role14.