The Critical Importance of Financial Literacy in Early Childhood (Ages 3-8)

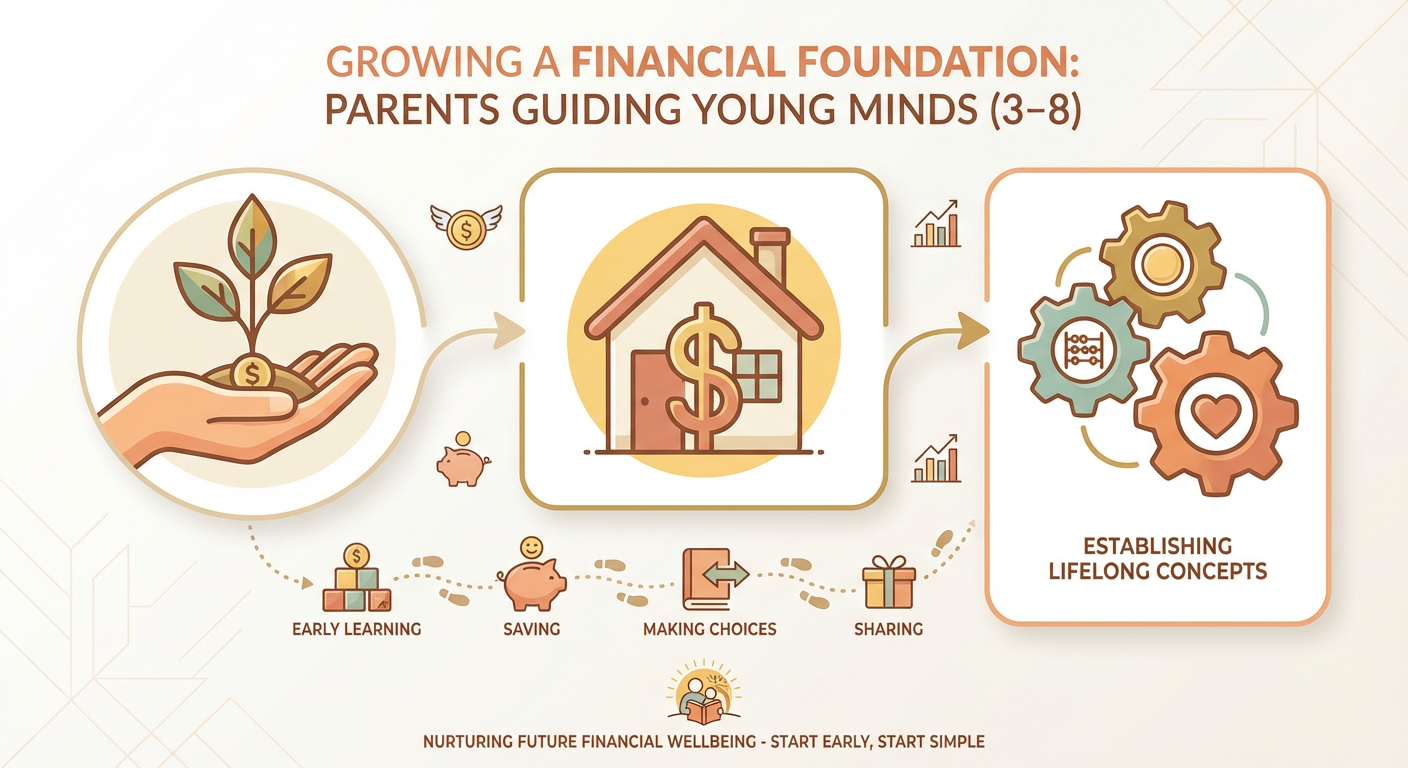

The foundation of lifelong financial well-being is not laid in high school or adulthood but in the formative years of early childhood. This comprehensive report delves into the compelling necessity of cultivating financial literacy in children aged 3 to 8, a crucial developmental window when basic money concepts are grasped and core financial habits are indelibly shaped. Drawing upon cutting-edge research, we examine how early exposure to financial principles, coupled with active parental involvement and age-appropriate educational strategies, can significantly influence a child’s future financial trajectory, fostering resilience, responsibility, and informed decision-making.

As societal complexities increase and economic landscapes evolve, the traditional reactive approach to financial education is proving insufficient. This report synthesizes global findings that highlight a growing parental awareness and a powerful youth-driven demand for earlier, more comprehensive financial instruction. We explore the profound impact of parental guidance as the ‘first financial classroom,’ providing insights into effective allowance strategies and communication techniques that transform everyday interactions into impactful learning opportunities. Furthermore, we analyze the current policy landscape, identifying both progress and persistent gaps in formal financial education for the youngest learners, while underscoring the long-term benefits that extend from higher credit scores to improved overall financial stability in adulthood.

Key Takeaways

- Early Habits Form Quickly: Children begin grasping money concepts by age 3, with core financial habits established by age 7, making early intervention critical.

- Parents Are Primary Educators: A significant 72% of parents acknowledge responsibility for financial education, engaging in discussions with 97% of their children.

- Allowance is Common, But Guidance Lacks: While 71% of parents give allowances, half struggle to explain complex financial concepts in an age-appropriate manner.

- Youth Demand More Education: Financial education ranks as the second-most desired reform by students globally, signaling a clear need for practical money skills.

- Policy Momentum Growing: 25 U.S. states now mandate personal finance in high school, but early elementary grades often lack formal requirements.

- Proven Long-Term Benefits: Early financial education correlates with higher credit scores and lower debt delinquency rates in adulthood.

- Critical Developmental Window: Ages 3-8 are vital for shaping positive attitudes towards money, emphasizing concrete, play-based learning over abstract concepts.

1. Executive Summary

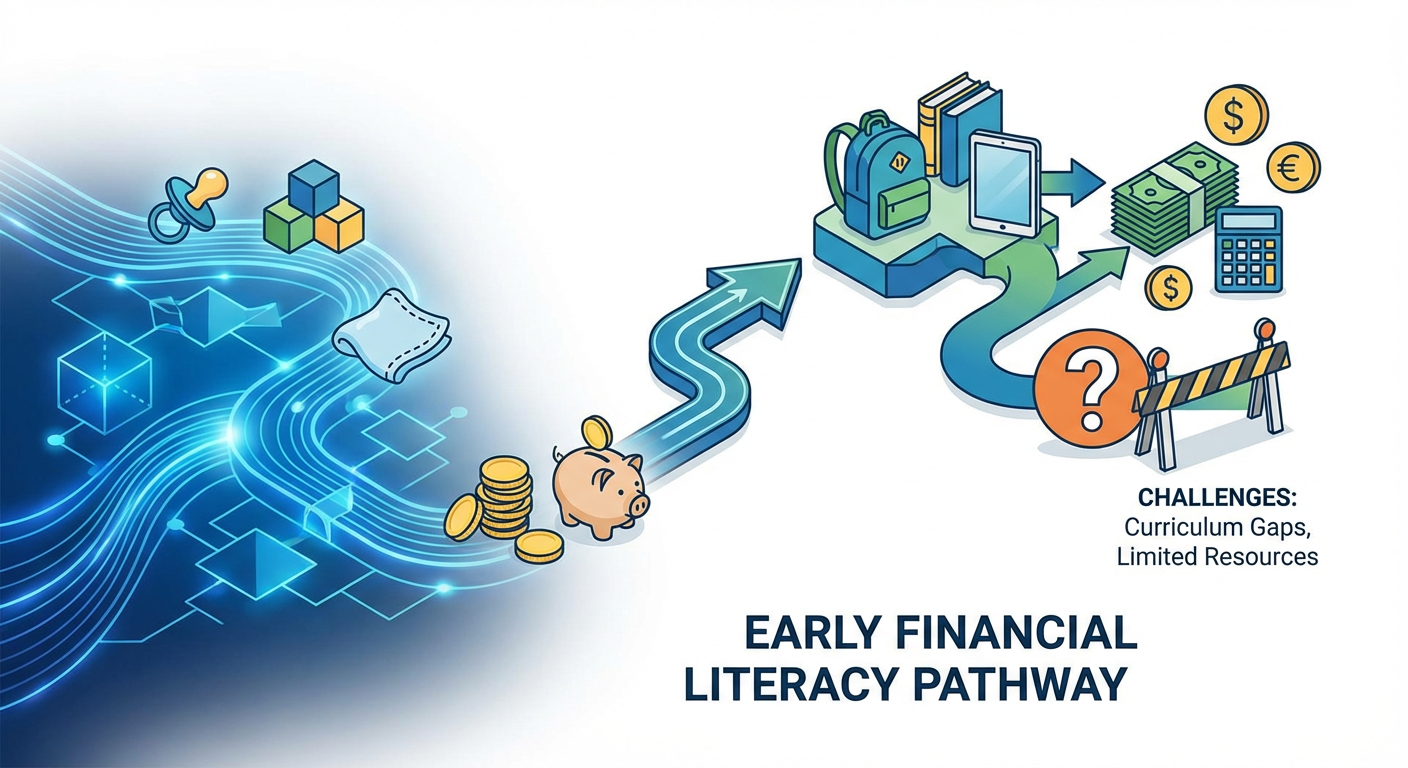

The landscape of financial education is undergoing a transformative shift, driven by a growing recognition that an early introduction to monetary concepts is paramount for fostering lifelong financial well-being. This executive summary critically examines the pressing importance of cultivating financial literacy in children aged 3 to 8 years old, drawing upon key research findings that highlight parental involvement, evolving educational trends, and the indelible long-term benefits of early intervention. Traditionally, financial education has been largely confined to older age groups, often integrated into high school curricula or addressed in adulthood reactively. However, compelling evidence now suggests that foundational money habits and attitudes are established much earlier in life, creating a critical window of opportunity during the formative years of early childhood.

Research conclusively demonstrates that children begin to grasp basic money concepts as early as age 3, with many of their core financial habits solidified by age 7[1]. This fundamental insight underscores the urgency of integrating financial lessons into early childhood development, positioning these years not merely as a precursor to formal learning, but as a crucial period for laying the groundwork of financial acumen. Waiting until adolescence to impart such vital skills risks missing the prime developmental stage when children are most receptive to internalizing behaviors and attitudes. A profound global survey conducted in 2025 revealed that a significant 72% of parents acknowledge their personal responsibility in educating their children about money, with an overwhelming 97% reporting some level of financial discussion with their offspring[2]. This data signifies a compelling and positive shift in parental awareness and engagement, indicating that contemporary parents increasingly view themselves as their children’s primary financial educators. However, this commitment is not without its challenges. While the practice of giving children an allowance is widespread, with 71% of parents with children aged 5–17 providing an average of $37 per week, approximately 50% of these parents concede to struggling with the articulation of complex financial concepts in an age-appropriate manner[3], [4]. This communication gap highlights a critical need for accessible resources, tools, and pedagogical strategies designed to empower parents in effectively translating financial principles into understandable lessons for young minds.

Beyond the domestic sphere, there is a discernible global demand for enhanced financial literacy education from the youth themselves. A 2023 global survey encompassing 37,000 students across 150 countries identified improved financial education as the second-most desired educational reform, cited by 59% of students, trailing only technology education in priority[5]. This youth-driven impetus is gradually catalyzing policy responses, albeit predominantly in later educational stages. As of 2024, 25 U.S. states mandate at least one semester of personal finance in high school, a substantial increase from just 8 states in 2020[6]. While this policy momentum is encouraging, it frequently bypasses early elementary grades, highlighting a prevailing gap in formal educational provisions for younger children. Nonetheless, the proven long-term benefits of financial education, including higher credit scores and lower debt delinquency rates among young adults who have received such instruction, reinforce the argument for earlier and more comprehensive integration throughout the educational continuum[7]. The objective of this summary is to synthesize these findings and articulate a compelling case for prioritizing early financial literacy education for children aged 3 to 8, recognizing its profound impact on individual, familial, and societal financial health.

1.1 The Crucial Window of Early Childhood: Shaping Lifelong Financial Habits

The most compelling argument for early financial literacy for kids is grounded in neurodevelopmental research, which identifies the period between ages 3 and 8 as a critical window for habit formation. Studies, such as those conducted by Cambridge University and cited by PBS, unequivocally state that children begin to understand basic money concepts by age 3, and critically, many of their core money habits are already established by age 7[8]. This means that fundamental attitudes towards saving, spending, and the value of money are not abstract concepts introduced in adolescence but are rather deeply ingrained behaviors formed during preschool and early elementary years. If a child passively observes a parent making impulsive purchases or experiences a lack of discussion around financial planning, these early observations can inadvertently shape their own financial predispositions.

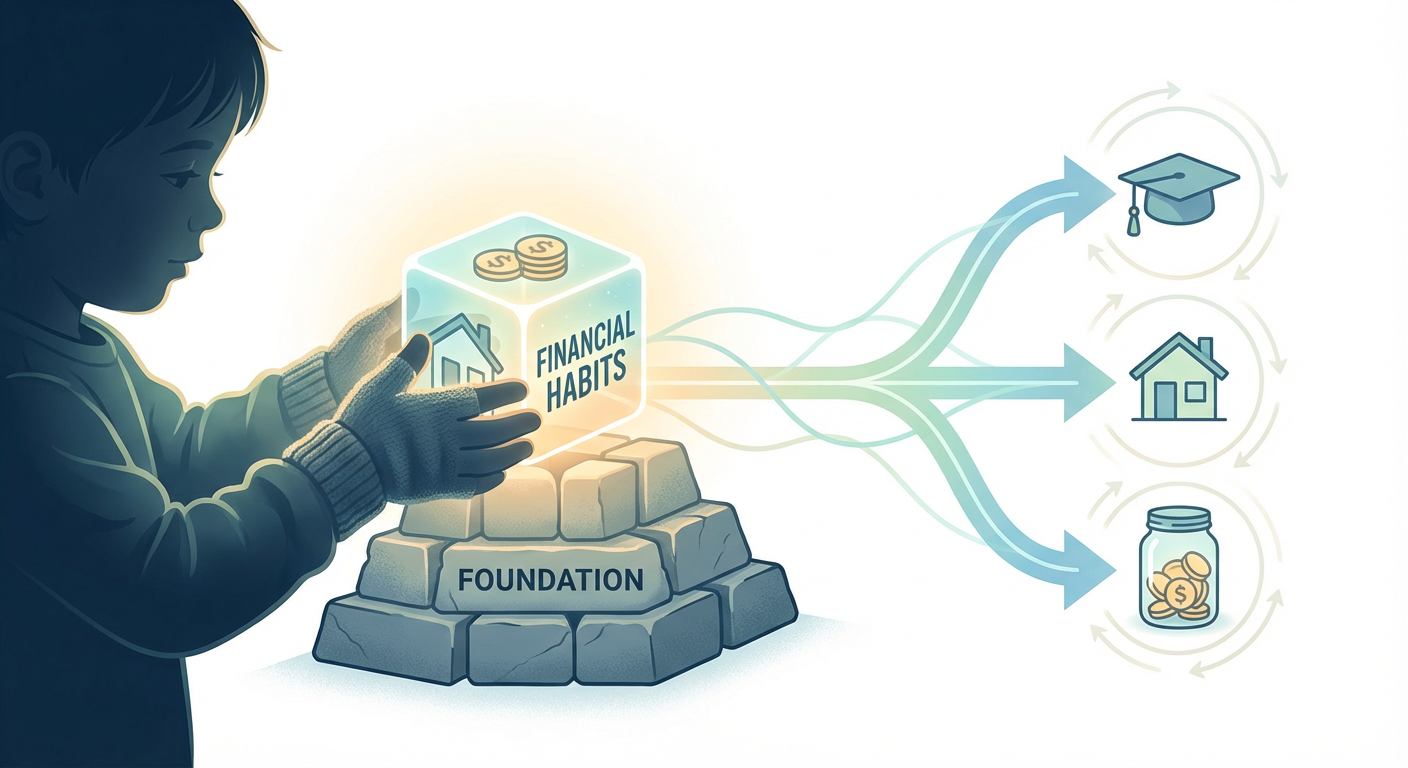

Conversely, children who are exposed to intentional financial lessons during this formative period are more likely to develop positive money habits that persist into adulthood. The analogy often drawn is that just as reading and arithmetic are taught early because literacy and numeracy build cumulatively over years, financial literacy also has a “prime learning time” in early childhood for foundational skills[9]. Missing this critical window can make it significantly harder to rectify ingrained poor habits or alleviate financial anxieties developed during youth. For instance, a child who never learns the concept of delayed gratification by saving for a desired item may grow into an adult prone to instant gratification and unchecked spending. The long-term payoff is substantial: individuals who receive early financial education tend to exhibit better financial outcomes, including higher savings rates and improved net worth in their late 20s[10]. This underscores the proactive nature of early financial literacy as an investment in a child’s future resilience and prosperity.

However, the early introduction of financial concepts necessitates an age-appropriate approach. For children aged 3-5, lessons should be concrete and experiential, focusing on simple concepts like coin recognition, distinguishing between needs and wants, and the basic exchange of money for goods. More abstract topics like credit, insurance, or complex investments are beyond their developmental stage and could lead to confusion or disengagement. The emphasis should be on play-based learning, storytelling, and interactive activities that make money concepts tangible and relevant to their world. A nuanced understanding is essential; for example, a study in Ghana found that purely financial lessons for young children could unintentionally encourage them to work more at the expense of their schooling, highlighting the importance of balancing financial education with social and developmental considerations[11]. The goal is to cultivate positive financial behaviors and a healthy relationship with money, not to induce premature engagement in complex financial systems.

1.2 The Pivotal Role of Parental Involvement: The Home as the First Financial Classroom

Parents are increasingly recognizing their indispensable role as the primary architects of their children’s financial understanding. The 2025 Ameriprise survey highlighted that a substantial 72% of parents feel personally responsible for teaching their children about money, and almost all (97%) engage in financial discussions with their children to some degree[12], [13]. This represents a significant evolution from previous generations, where financial topics were often considered taboo or simply not discussed within the family unit. Historically, a concerning 18% of U.S. adults reported never receiving any financial education from their parents, and this gap was particularly pronounced among women (22% of female respondents vs. 15% of males)[14], [15]. Modern parents, driven by an awareness of economic uncertainties and a wealth of accessible resources, are actively striving to bridge these historical gaps and prioritize financial literacy as a core component of their children’s upbringing.

The home environment serves as an invaluable, organic laboratory for financial learning. Children are keen observers, and they absorb financial behaviors by watching their parents navigate everyday monetary decisions. Therefore, parents can transform routine activities—such as grocery shopping, paying bills, or using an ATM—into teachable moments. Experts recommend that parents narrate their financial actions, explaining, for example, “We’re using a coupon to save money,” or “I pay this bill monthly so we can have electricity.”[16] These ongoing conversations normalize financial discussions, demystify money, and help children understand the practical applications of financial concepts within a real-world context. Children who regularly engage in such discussions with their parents tend to exhibit higher financial literacy measures and greater confidence in managing money as they grow older[17].

Allowance systems remain a prevalent and effective pedagogical tool. With 71% of parents already providing allowances, typically starting between ages 5 and 8, this practice offers a tangible “income” for children to manage[18]. The most impactful allowance strategies extend beyond mere remuneration, instead becoming structured learning opportunities. Many families adopt approaches where children are encouraged to divide their allowance into distinct categories such as “Spend,” “Save,” and “Donate,” often utilizing physical jars or digital apps. Some parents link allowances to chores, establishing a direct connection between effort, work, and monetary reward. For instance, the Stern family in San Diego implemented an “earn and learn” system, paying their sons for additional tasks beyond basic responsibilities, thereby teaching the valuable lesson that money is earned through effort and is finite[19]. This experiential learning fosters budgeting skills, delayed gratification, and a deeper appreciation for the value of money.

Furthermore, contemporary parental involvement is actively addressing historical gender biases in financial education. Parents are now encouraged to involve all children, regardless of gender, in household financial activities, thereby ensuring equitable skill development. The past disparity, where 22% of women reported no childhood financial education compared to 15% of men, serves as a poignant reminder of the need for intentional, inclusive financial socialization[20]. By actively engaging both boys and girls in discussions about budgeting, saving, and making informed financial choices, parents can cultivate confidence and competence in all their children, laying the foundation for greater financial equality in the future. Financial institutions and educational organizations play a crucial supporting role by providing parents with accessible resources, conversation guides, and age-appropriate tools to facilitate these essential money discussions at home.

1.3 The Expanding Ecosystem of Support: Schools, Policy, and Community Initiatives

While parental influence is undeniably central, the broader societal ecosystem — encompassing schools, policymakers, and community organizations — is increasingly recognizing its role in cultivating early financial literacy. Historically, formal financial education has been largely confined to secondary or tertiary education, if integrated at all. However, a significant policy shift is underway in the United States, where 25 states now mandate a high school personal finance course, a remarkable 212% increase since 2020[21]. Although this momentum primarily focuses on older students, it signals a broader political and educational acknowledgment of financial literacy’s importance, which observers anticipate will eventually “trickle down” to earlier grades.

Internationally, there is a growing consensus, championed by organizations like the OECD, that financial education should commence in primary school and be integrated continuously throughout a child’s educational journey[22]. This guidance is inspiring ministries of education globally to explore age-appropriate financial literacy modules for younger students. Initiatives like Global Money Week, an annual campaign engaging over 170 countries, often include activities designed for elementary-aged children, utilizing interactive approaches such as bank field trips or school savings clubs to make learning about money engaging and relevant. Programs like the “Cha-Ching” curriculum in Asia, which employs animated music videos and classroom activities to teach core financial concepts—Earn, Save, Spend, and Donate—have demonstrated remarkable success. For instance, in the Philippines, this program is projected to have reached 1 million students by the 2023–2024 school year, exemplifying how creative, age-tailored content can achieve widespread impact[23], [24]. These international examples highlight the potential for scalable solutions when educational content is thoughtfully designed for young learners.

Despite this global momentum, implementing early financial literacy in schools faces practical challenges. Many primary school teachers may feel ill-equipped to teach financial topics without specialized training, and the already crowded curriculum presents a barrier to adding new standalone subjects. To overcome these hurdles, innovative approaches are being adopted, such as integrating financial concepts into existing subjects—for instance, using money-related word problems in math class or role-playing economic scenarios in social studies. Furthermore, ensuring that educational materials are developmentally appropriate is crucial; while abstract financial instruments are unsuitable for young children, tangible concepts like differentiating between “needs” and “wants” can be effectively introduced to children as young as six. Addressing these challenges will require robust teacher training, the development of engaging, play-based pedagogies, and collaborative efforts between educational institutions and financial sector organizations.

Community and industry support are vital components of this expanding ecosystem. Financial institutions and non-profit organizations frequently sponsor programs that deploy volunteers to elementary classrooms, provide free lesson plans, or host educational events during periods like Financial Literacy Month. These collaborations often offer resources that complement parental efforts, creating a more comprehensive learning environment. For example, the “For Me, For You, For Later” program, a partnership between Sesame Workshop and PNC Bank, developed bilingual educational kits featuring beloved Muppet characters to teach preschoolers about spending, sharing, and saving[42]. Distributed through libraries, schools, and bank branches, this initiative reached hundreds of thousands of families, offering a playful and relatable entry point into financial concepts for children as young as three. These community-led initiatives not only enhance financial literacy but also underscore the collective responsibility of various stakeholders in nurturing financially capable future generations.

1.4 Effective Pedagogies: Learning by Doing for Ages 3-8

For children aged 3 to 8, effective financial literacy education hinges on experiential, play-based learning that makes abstract concepts tangible and relatable. Young children are inherently hands-on learners, and instructional strategies should leverage their natural curiosity and desire for engagement rather than relying on abstract lectures. The overarching principle is that children learn finance best by “doing” with appropriate guidance; every interaction with money, whether real or simulated, serves as a building block for future understanding.

Play-based Learning and Gamification: Successful programs often integrate games, role-play, and interactive activities. For instance, setting up a “pretend store” in a classroom or at home allows children to practice using play money, understanding pricing, and making change in a low-stakes, fun environment. Board games like “Cashflow for Kids” introduce concepts such as investing and saving in a simplified format, making complex financial ideas accessible to younger audiences[25]. Mobile applications tailored for children also offer gamified approaches, enabling kids to manage virtual allowances, track savings goals, and understand spending decisions under parental supervision. Through these methods, children as young as 5 or 6 can begin to internalize principles like earning (linking effort to reward), saving (accumulating resources for a larger goal), and smart spending (making choices within limited resources).

Chore and Reward Systems: Tying money to chores or tasks is a widely recommended practice for teaching the fundamental connection between work and income. This system helps children understand that money is not an endless resource but is earned through effort and contribution. The Stern family’s “earn and learn” model, where children receive payment for extra chores and community service beyond their basic responsibilities, exemplifies this approach. This not only teaches the value of hard work but also introduces budgeting, as children learn to manage variable income and prioritize their spending and saving decisions[26]. Such systems help cultivate an important mindset that money is finite and requires deliberate planning.

Saving Tools: From Piggy Banks to Digital Apps: The ubiquitous piggy bank remains an effective tool for teaching saving to younger children. Clear piggy banks or those with segmented compartments (e.g., “Save,” “Spend,” “Donate”) visually reinforce money allocation concepts. In the digital age, secure money management apps for children, such as Greenlight or GoHenry, offer modern alternatives. These apps, typically controlled by parents, allow children to see their account balances grow with savings and decrease with spending, providing real-time feedback on their financial decisions. Many platforms incorporate kid-friendly interfaces, interactive lessons, or quizzes. Greenlight, for example, allows children to set savings goals and even engage in small, parent-approved investments, transforming abstract financial concepts into concrete experiences that motivate continued saving[27]. For the youngest demographic (3–5 years), simple sticker charts to track savings toward a desired treat can lay the groundwork for later digital engagement.

Stories, Media, and Real-Life Transactions: Children’s literature and educational media are powerful conduits for conveying financial lessons. Picture books exploring themes of earning, saving, and distinguishing needs from wants (e.g., “Curious George Saves His Pennies”) make these concepts relatable. Iconic children’s programs, such as Sesame Street, have also integrated financial basics into their content. The “For Me, For You, For Later” initiative, for example, leveraged beloved Muppet characters to demonstrate spending, saving, and sharing to preschoolers through videos and storybooks. This use of familiar narratives and characters helps demystify financial concepts, allowing children to connect with situations where characters make financial choices and experience the consequences. In reinforcing these lessons, parents can involve children in small, real-life transactions: allowing a 6-year-old to hand cash to a cashier and receive change, or permitting a 7-year-old to select an item within a pre-set budget. These mini-experiences build confidence, teach about currency value, and foster decision-making skills.

Furthermore, opening a simple savings account (often joint with a parent) can significantly reinforce saving habits. Research shows that children with a savings account, even with a modest balance, are more likely to develop sustained saving habits and pursue higher education later in life[28], [29]. This demonstrates that experiential learning, coupled with tangible tools and engaging content, is the most effective approach to instilling foundational financial literacy in children aged 3-8, cultivating skills and mindsets that will serve them throughout their lives.

1.5 Lifelong Impact: The Far-Reaching Benefits of Early Financial Literacy

The ultimate rationale for investing in early financial literacy for children aged 3 to 8 lies in its profound and enduring lifelong impact, shaping not only individual financial health but also contributing to broader societal well-being. The benefits extend far beyond merely understanding money to influence personal trajectories in education, career, and overall economic stability.

Improved Financial Outcomes as Adults: There is compelling evidence linking early financial education to demonstrably better financial outcomes in adulthood. Longitudinal studies in the U.S. indicate that individuals who received personal finance instruction, even if introduced later in their teenage years, exhibit significantly better financial behaviors. For instance, young adults in states with mandated financial education courses showed lower credit delinquency rates (1-3% lower) and higher credit scores (often 10-20 point increases by their early 20s) compared to their peers without such education[30]. Starting this education even earlier, during the foundational years of 3-8, provides an extended runway for children to internalize these habits, potentially leading to even more pronounced and positive cumulative advantages throughout their lives. The earlier the foundation is laid, the greater the likelihood of robust financial resilience in adulthood.

Enhanced Educational and Career Trajectories: Early financial literacy also plays a critical role in shaping educational and career aspirations. Children who grasp concepts of saving and investing in themselves are more inclined to pursue higher education or vocational training. Research on Children’s Savings Account (CSA) programs underscores this link: even a small, dedicated college savings fund can dramatically increase a child’s likelihood of attending and completing college. Studies have found that low-to-moderate-income children with less than $500 saved for college were approximately three times more likely to enroll, and those with $500 or more saved were about four times more likely to graduate, compared to those with no savings[31], [32]. This demonstrates that the act of saving early on cultivates not only a financial asset but also a powerful mindset of investing in one’s future, influencing long-term educational and career choices.

Promoting Economic Inclusion and Social Mobility: Financial literacy is increasingly recognized as a vital tool for fostering economic equity and social mobility. Children from disadvantaged backgrounds, without access to early financial guidance, may face a double disadvantage: a lack of inherited wealth compounded by a deficit in financial knowledge. Early interventions can help bridge this gap. Programs targeting young children in underserved communities, such as school-based banking initiatives or games teaching entrepreneurship, have shown promise in boosting savings behaviors and financial confidence[33]. Over time, these micro-level changes can contribute to macro-level improvements, including higher rates of bank account ownership, reduced susceptibility to predatory financial practices, and an enhanced capacity to accumulate assets. In essence, financial literacy acts as a form of human capital; much like early reading skills contribute to higher lifetime earnings, early financial literacy can significantly enhance economic stability and upward mobility, especially for vulnerable populations.

Multiplier Effect on Families and Communities: The impact of early financial literacy extends beyond the individual child, creating a positive multiplier effect within families and communities. When children learn about money concepts, they often engage their parents in discussions, prompting caregivers to re-evaluate or expand their own financial knowledge. A child’s direct inquiries about topics like needs vs. wants can initiate household discussions about budgeting or savings goals. Financially literate adults are also less likely to require financial support from wider family networks, contributing to the overall resilience of the family unit. This ripple effect signifies that early financial education is not merely an individual endeavor but a collective investment that can uplift entire communities. Moreover, a generation that is financially literate from childhood is likely to become more responsible consumers and informed citizens, making more prudent decisions regarding personal debt, investments, and economic participation. This shift contributes to a more stable and prosperous society, validating the OECD’s conclusion that teaching financial skills early is “an investment that pays dividends for life” for individuals, economies, and society at large[34].

1.6 Key Data Points and Statistics Supporting Early Financial Literacy

The imperative for early financial literacy is substantiated by a robust body of research and compelling statistics. These data points collectively underscore the necessity of formal and informal financial education for children aged 3-8:

- Early Habit Formation: Children begin to grasp basic money concepts by age 3, and critical money habits are largely established by age 7[8] (Cambridge University study, cited by PBS, 2018).

- Parental Responsibility: A 2025 global survey found that 72% of parents feel personally responsible for teaching their children about money, with 97% reporting at least some financial discussion with their kids[12], [13] (Ameriprise Financial, 2025).

- Allowance Prevalence & Challenge: 71% of parents (with kids aged 5-17) provide an allowance, averaging $37 per week[18]. However, approximately 50% of these parents admit they struggle to explain financial concepts in an age-appropriate way[4] (Wells Fargo survey, 2023).

- Youth Demand: A 2023 global survey of 37,000 students across 150 countries revealed that 59% desire more financial literacy education in school, making it the second-most requested curriculum reform after technology education[5].

- Policy Momentum: As of early 2024, 25 U.S. states mandate a personal finance course for high school graduation, a significant increase from just 8 states in 2020[6]. This represents a 212% increase in state mandates within four years.

- Lifelong Benefits: Students who receive personal finance instruction demonstrate higher credit scores (10-20 point increases) and lower debt delinquency rates (1-3% lower) as young adults[7] (Financial Literacy and Education Commission, various studies).

- Saving Potential: Children often save a significant portion of their allowance; an analysis of family allowance apps showed kids saved roughly 43% of their allowance on average in 2022, up from 38% in 2019[27], [35] (RoosterMoney data, 2022).

- Global Financial Illiteracy: Only about 33% of adults globally are considered financially literate[36] (S&P Global FinLit Survey, 2015).

- Gender Gap in Home Education: Among U.S. adults, 22% of women reported receiving no childhood financial education from parents, compared to 15% of men[15] (CardRatings.com survey, 2023).

- Impact of Children’s Savings Accounts: Low-to-moderate-income children with less than $500 saved for college were approximately 3 times more likely to enroll, and those with $500+ saved were 4 times more likely to graduate[31], [32].

These data collectively paint a clear picture: early childhood is a critical period for financial habit formation, parents are increasingly eager to teach, and effective, age-appropriate educational strategies, supported by policy and community efforts, yield substantial and lasting positive outcomes for individuals and society.

The preceding analysis unequivocally establishes the critical importance of early financial literacy for children aged 3-8. The subsequent sections of this report will delve deeper into specific aspects of this topic, beginning with an exploration of the theoretical frameworks guiding early childhood financial education, followed by detailed examinations of practical strategies for parents and educators, and discussions on policy implications and future directions.

2. The Formative Years: Why Financial Habits are Built by Age 7

The journey towards financial literacy is often perceived as a late-stage educational endeavor, typically relegated to high school curricula or the precipice of adulthood. However, an accumulating body of research unequivocally demonstrates that the foundational bricks of financial understanding and behavior are laid much, much earlier in life. Indeed, the period between ages 3 and 8 represents a critical, formative window where children begin to grasp fundamental money concepts and, crucially, establish core financial habits that can significantly influence their long-term economic well-being. This section delves deeply into the scientific basis for early financial education, highlighting why these years are a ‘prime learning time’ and exploring the profound, enduring payoffs of early intervention.

The notion that basic money concepts are understood by age 3 might initially seem counterintuitive. Conventional wisdom often assumes that such abstract thinking is beyond the capacity of preschoolers. Yet, studies, including a significant Cambridge University study for the UK’s Money Advice Service, have revealed that very young children process information about value and exchange at a remarkably early age. By age 3, children can recognize coins and understand the elementary principle of trading money for goods [1]. This early cognitive ability to understand transactional relationships forms the bedrock upon which more complex financial ideas will later be built. The subsequent years, up to age 7, are then crucial for solidifying these nascent understandings into ingrained habits. By this pivotal age, many core money habits, such as tendencies towards saving or spending, are already firmly established [1].

This early habit formation is not merely anecdotal; it is a profound developmental insight with significant implications for educational strategies. Just as early childhood is recognized as a vital period for language acquisition and social-emotional development, it is increasingly being seen as equally important for financial socialization. The argument is simple yet powerful: if crucial life habits are formed by age 7, waiting until the teenage years to introduce formal financial education may be a missed opportunity, akin to expecting a child to read fluently without early exposure to phonics and words. This section will meticulously examine the research supporting this perspective, explore the multifaceted influences shaping these early habits, and articulate why investing in financial literacy for children aged 3-8 is an investment in a more financially secure future.

2.1 The Critical Window: Money Concepts by Age 3, Habits by Age 7

The scientific understanding of childhood development has long underscored the plasticity of the young brain and the profound influence of early experiences on lifelong traits. In the realm of financial literacy, this principle holds particularly true. Research indicates that children are far more capable of absorbing monetary concepts at a young age than previously assumed, and these early exposures significantly contribute to the formation of enduring financial behaviors.

A seminal study conducted by researchers at Cambridge University, cited by PBS, provides compelling evidence that children begin to understand fundamental aspects of money as early as age 3 [1]. At this stage, cognitive abilities are developing rapidly, allowing children to recognize the physical attributes of currency (e.g., distinguishing a coin from a button), and to grasp the basic concept of exchange—understanding that money is given in return for goods or services. This intuitive understanding of ‘value’ and ‘transaction’ is foundational, even if rudimentary. As children progress to ages 5, 6, and 7, their cognitive capabilities expand, enabling them to comprehend more nuanced ideas such as delayed gratification, the purpose of saving, and the distinction between needs and wants. For instance, a first grader can often understand the concept of putting aside money to purchase a desired toy at a later date [1].

The apex of this early learning curve, according to the Cambridge University study, is around age 7, by which time many of a child’s core financial behaviors are already established [1]. These behaviors include tendencies towards saving, impulsivity in spending, and even attitudes towards sharing. This finding suggests that these behaviors are not merely temporary childhood quirks but are deeply ingrained predispositions that can persist into adulthood. The study highlights that the ‘prime learning time’ for financial habits parallels that for other critical life skills, such as reading, where early exposure translates into greater proficiency and confidence down the line [17]. An analogy often used is that just as we teach reading early because literacy builds over years, financial literacy’s “prime learning time” is in early childhood for foundational skills [17].

The implications of this research are far-reaching. If core money habits crystallize by age 7, then interventions or educational efforts initiated much later, such as in high school, may face significant challenges in reshaping deeply entrenched patterns. While later education can certainly provide valuable knowledge and strategies, its ability to alter fundamental behavioral tendencies might be limited compared to interventions during the formative years. This is not to say that financial education at later stages is ineffective, but rather that it builds upon a foundation (or lack thereof) established much earlier. The absence of early guidance can lead to the development of undesirable habits or anxieties around money, which can be difficult to undo later in life [8].

For example, a child who consistently receives instant gratification for every desire without understanding the concept of saving might grow into an adult prone to impulsive spending and debt accumulation. Conversely, a child who learns to save a portion of their birthday money from a young age is more likely to develop that routine as second nature, carrying it into adulthood [17]. Statistics underscore the potential long-term impact: a global survey from 2015 found that only 1-in-3 adults is financially literate across the world, a deficit many experts attribute to a lack of early exposure to financial education [18]. Early intervention, therefore, is not merely beneficial; it is essential for cultivating a generation with robust financial literacy.

However, it is crucial that the approach to early financial education is age-appropriate. While very young children can grasp basic concepts, formal economics or complex financial products are far beyond their developmental capacity. For ages 3-5, lessons should be concrete and experiential, focusing on activities like identifying coins, understanding that money is exchanged for goods, or the simple act of choosing between two items with limited funds. The key is integrating learning through play and gradual introduction, avoiding pressure or anxiety around money. A cautionary example from Ghana, where a study found that purely financial lessons inadvertently led some children to work more (to earn money) at the expense of schooling, highlights the importance of balancing financial instruction with social lessons to mitigate unintended negative consequences [19]. The nuance lies in fostering good habits through play and practical experience, without promoting materialism or misinterpreting the value of money in relation to other life aspects.

By understanding and leveraging this critical developmental window, parents, educators, and policymakers can create environments where children not only learn about money but also internalize prudent financial behaviors from preschool, setting the stage for a lifetime of informed financial decision-making.

2.2 The Parent’s Influence: Home as the First Finance Classroom

While schools and formal educational programs play an increasingly vital role in financial literacy, the home environment remains the primary crucible where a child’s earliest and most impactful financial lessons are forged. Parents, by virtue of their constant presence and modeling, are undeniably their children’s first and most influential financial educators. The financial behaviors, attitudes, and conversations children witness and participate in at home profoundly shape their understanding of money and their own future financial habits.

This significant parental role is widely recognized by modern parents. A global survey conducted in 2025, involving approximately 3,000 parents worldwide, revealed that a substantial 72% feel personally responsible for teaching their children about money [20]. Furthermore, an overwhelming 97% of parents reported engaging in financial discussions with their children at least occasionally [20]. This represents a notable shift from previous generations, where discussions about money were often considered taboo or simply not prioritized. Historically, 18% of U.S. adults surveyed stated they received no financial education from their parents, and this figure was even higher for women, with 22% of female respondents reporting a lack of early financial guidance compared to 15% of males [10]. The modern parental recognition of their responsibility reflects a growing awareness of the importance of financial skills in an increasingly complex economic world, and a desire to better prepare their children for it.

The impact of parental modeling cannot be overstated. Children are keen observers, and they absorb financial behaviors by watching their parents navigate everyday situations. Routine activities such as grocery shopping, paying bills, using credit cards, or making decisions about household budgets become invaluable teachable moments. Experts recommend that parents actively narrate these activities, explaining the rationale behind financial choices. For example, a parent might explain, “We’re using this coupon because it helps us save money,” or “I pay the electricity bill each month so we can have lights” [21]. These simple explanations demystify money management and illustrate the practical application of financial principles. Normalizing discussions about saving goals, budgets, and even family financial constraints helps to alleviate the anxiety often associated with money and fosters an open environment for learning. Children who regularly discuss finances with their parents tend to score higher on financial literacy assessments during their teenage years and exhibit greater confidence in managing money independently [22].

One of the most common and effective tools parents employ for hands-on financial education is the allowance. A 2023 Wells Fargo survey found that 71% of parents with children aged 5-17 provide an allowance, averaging $37 per week, with many initiating this practice when children are between 5 and 8 years old [23]. This mini “income” provides children with a tangible resource to manage. The most beneficial allowance systems tie the money to deliberate lessons. For instance, many families encourage or require children to divide their allowance into distinct jars or accounts designated for “Spend,” “Save,” and “Donate.” This segmentation helps children visualize the different purposes of money and introduces foundational budgeting concepts. Another effective approach is connecting allowance to chores or tasks, thereby instilling the critical link between effort and earning. The Stern family in San Diego, for example, implemented an “earn and learn” system where their three sons (ages 5, 8, 11) receive payment for extra chores beyond their basic responsibilities, such as yard work or contributing to community service [24]. This method directly teaches that money is earned through labor, fostering a stronger work ethic and a more discerning approach to spending. While there is no universal “best” approach, the common thread is active parental guidance and involving children in decision-making regarding their own funds.

Despite the widespread use of allowances and the recognition of parental responsibility, a significant communication gap persists. Approximately 50% of parents who provide allowances admit to struggling with explaining financial concepts to their children in an understandable way [23]. This highlights a crucial area for support, as providing money is easier than effectively teaching its management. Parents require resources and confidence to convey lessons on budgeting, saving, or distinguishing between needs and wants to young children. This gap underscores the need for accessible, age-appropriate educational materials and guidance for parents themselves.

Addressing historical biases, particularly gender-based disparities in financial education, is also a critical aspect of parental influence. The past tendency for parents to discuss finances more extensively with sons than daughters has contributed to a gender gap in financial literacy and confidence. Modern parents are actively working to close this gap by intentionally involving all children in financial activities, whether it’s decision-making during grocery shopping or discussing savings for a family outing. Businesses and educators can support these efforts by providing gender-neutral resources such as conversation guides, storybooks, and interactive apps designed to facilitate inclusive discussions at home.

In essence, the home is a dynamic and ever-present financial laboratory for children. The financial culture established by parents, through their actions, conversations, and the tools they provide (like allowances), forms the fundamental framework for their children’s future financial capability. Recognizing and empowering parents as primary financial educators is therefore paramount to building a financially literate future generation.

2.3 Schools and Society: Integrating Financial Literacy into Early Education

While the home serves as the initial classroom for financial learning, the broader educational system and societal initiatives play an increasingly crucial role in supplementing and formalizing early financial literacy. Historically, formal financial education has been largely confined to later stages of schooling, typically high school. However, a growing consensus, supported by international bodies and policy trends, advocates for the integration of age-appropriate financial lessons into early elementary curricula. This shift recognizes the critical window of habit formation in early childhood and aims to build a more robust foundation for financial capability from the ground up.

The current state of financial literacy within formal education reveals a significant disparity. As of early 2024, approximately 25 U.S. states mandate at least one semester of personal finance instruction for high school graduation, a substantial increase from just 8 states in 2020, representing a 212% surge in mandates within four years [25]. This rapid expansion reflects a broader acknowledgement of financial literacy’s importance at a policy level, driven in large part by student demand and proven long-term benefits [5]. However, this momentum predominantly targets older students. Very few national curricula globally mandate financial literacy in early elementary grades. Where it does exist, it’s often woven into existing subjects like mathematics (e.g., counting coins, making change) or social studies (e.g., understanding markets, trade) rather than a standalone subject.

However, international organizations like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are actively advocating for earlier intervention. The OECD explicitly recommends that financial education begin early and be integrated throughout a child’s schooling, starting from elementary years onward [13]. This guidance emphasizes the importance of introducing age-appropriate money lessons in primary school, rather than deferring such critical instruction until high school. This international push is prompting education ministries worldwide to consider rolling out structured, age-appropriate financial literacy modules for younger students.

Global initiatives and policy trends further illustrate this growing emphasis on early financial education. Annual campaigns like Global Money Week, celebrated in over 170 countries, often feature activities tailored for elementary-aged children, including bank field trips, school savings clubs, and interactive workshops designed to make learning about money enjoyable. Pilot programs are emerging in various regions; for instance, some parts of Asia and Europe have seen governments partnering with Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) to deliver financial literacy workshops directly in primary schools. The UK, despite its formal personal finance education typically commencing in secondary school, has many primary schools voluntarily adopting programs from charities like Young Enterprise, which teach basic saving and budgeting concepts using play money. Moreover, innovation is evident in emerging markets, with countries like Kenya and Uganda introducing “school bank” programs where children can deposit small savings weekly, thereby fostering both mathematical skills and a savings habit from a young age [26]. The overarching policy trajectory is clear: financial capability is being recognized as a fundamental life skill, akin to literacy and numeracy, meriting its integration into education as early as possible.

Despite high-level support, the practical implementation of early financial literacy faces several challenges. A primary hurdle is that many primary school teachers may feel ill-equipped or lack the necessary training to effectively teach financial topics. This issue is often compounded by an already crowded curriculum, where adding new content competes with essential subjects like reading, mathematics, and science. To address these challenges, many successful programs adapt by integrating financial lessons into existing subjects rather than introducing entirely new ones. For example, math classes can incorporate story problems involving spending, saving, and making change, thereby reinforcing both mathematical and financial concepts simultaneously.

Another crucial implementation challenge is ensuring that educational materials are developmentally appropriate. Abstract financial concepts like credit, interest rates, or insurance are generally beyond the cognitive grasp of a 6- or 7-year-old. Therefore, curricula for this age group must focus on concrete ideas, such as distinguishing between “needs vs. wants,” the concept of earning money through effort, or the practice of saving for a specific goal. Education experts consistently emphasize the importance of robust teacher training and engaging pedagogical approaches—including storytelling, games, and interactive activities—to make these lessons effective and enjoyable for young learners. Furthermore, some countries are initiating outcome measurements, assessing whether children exposed to early financial lessons demonstrate improved numeracy or a greater understanding of economic principles, to strengthen the case for broader implementation.

Community and industry support are also critical for successful integration. Financial institutions and nonprofit organizations frequently collaborate with schools, sponsoring programs that send volunteers to elementary classrooms or providing free, well-designed lesson plans. Across Canada and in other nations, banks actively participate in financial literacy months by sending employees to schools to conduct classes on money basics. There’s also a growing recognition of the need for cultural tailoring and local relevance. Programs might adapt their content to reflect local currencies, customary saving practices, or community-specific economic contexts. The involvement of community organizations can prove invaluable in this regard, facilitating cultural adaptation and reaching younger children in informal settings such as community centers, libraries, and even children’s museums with interactive financial exhibits. As financial literacy moves towards becoming a universally acknowledged life skill, the collaborative efforts of schools, parents, governments, and businesses are increasingly extending to engage children in the crucial 3-8 age bracket.

2.4 Learning by Doing: Effective Methods to Teach Ages 3–8

For children aged 3–8, abstract lectures or complex theoretical explanations of finance are largely ineffective. Instead, learning by doing, through concrete experiences, play, and engaging narratives, is the most powerful pedagogical approach. Successful financial literacy programs and parental strategies for this age group prioritize hands-on interaction and relatable scenarios, transforming potentially daunting topics into accessible and enjoyable lessons.

2.4.1 Play-Based Learning

Play is a child’s natural mode of learning and exploration. Integrating financial concepts into play activities can make these ideas concrete and memorable. A common and highly effective classroom activity is setting up a “pretend store” where children use play money to buy and sell items, practicing price recognition, counting, and making change. This experiential learning allows them to internalize the transactional nature of money in a safe, low-stakes environment. Similarly, board games designed with financial themes, such as a simplified version of “Monopoly” or “Cashflow for Kids” (which introduces concepts like investing and saving in a fun, accessible format), help children grasp ideas like earning, saving, and spending through interactive engagement [27]. Through such play, children as young as five or six can begin to understand the idea of earning through effort, the concept of saving for a larger goal, and the critical skill of making choices with limited resources.

2.4.2 Chore and Reward Systems

Many experts advocate for tying monetary rewards to chores or tasks, which directly teaches the fundamental connection between work and income. Even a five-year-old can comprehend that effort leads to reward. The Stern family of San Diego offers a compelling example: their three sons (ages 5, 8, and 11) engage in an “earn and learn” system, where they receive payment for additional chores beyond their routine responsibilities, such as washing the car or picking up park litter. This system empowers the children to understand that money is earned and encourages them to be more discerning about their spending choices [28]. For instance, their eight-year-old saved his chore money for months to purchase a specific LEGO set, fostering a profound sense of accomplishment and demonstrating the principle of delayed gratification. This method not only teaches earning and budgeting but also reinforces the vital mindset that money is a finite resource directly linked to effort and contribution.

2.4.3 Saving Tools: From Piggy Banks to Apps

Visual and tangible saving tools are crucial for young learners. The classic piggy bank remains an effective starting point for preschoolers and early elementary children. Clear piggy banks or those with partitioned sections (e.g., “Save,” “Spend,” “Donate,” “Invest”) help children visualize how money can be allocated for different purposes. In the digital age, innovative apps like Greenlight or GoHenry offer modern alternatives. These parent-controlled platforms allow even young children to track their “account” balances, seeing their money grow with savings and diminish with spending, all under parental supervision. Many of these apps feature kid-friendly interfaces, interactive lessons, and quizzes that reinforce financial concepts. Parents report that seeing their savings totals visually displayed can be a powerful motivator for children to achieve financial goals. Greenlight, for example, allows children to set savings goals and even engage in small, parent-approved investments, making abstract financial concepts more concrete and relatable [29]. For the youngest age group (3-5 years), analog methods such as sticker charts linked to saving coins for a special treat can effectively lay the groundwork, gradually transitioning to digital tools as they mature.

2.4.4 Stories and Media

Children’s literature and media are powerful vehicles for conveying financial lessons in an engaging and accessible manner. Picture books that explore themes like earning, saving for a special item, or distinguishing between needs and wants (e.g., “Curious George Saves His Pennies” or “Bunny Money”) provide relatable narratives that resonate with young children. A notable initiative is the “For Me, For You, For Later” program launched by Sesame Workshop (creators of Sesame Street) in partnership with PNC Bank in 2011. This bilingual financial education program utilizes beloved Muppets like Elmo and Cookie Monster in videos and storybooks to introduce basic money ideas: spending, sharing, and saving. Free kits, including storybooks, parent guides, and activity workbooks, were distributed to hundreds of thousands of families and schools across the U.S. The program successfully provided parents with a comfortable framework (the “Three S” approach: Spend, Share, Save) to discuss money with their preschoolers. Evaluations indicated that children who engaged with the content were better able to identify coins and articulate the meaning of saving [30]. This demonstrates the power of familiar characters and narratives to demystify complex ideas for a pre-Kindergarten audience, while also emphasizing a crucial best practice: educating parents alongside children to reinforce lessons within the home environment.

2.4.5 Real Transactions and Mini-Experiences

Nothing solidifies learning quite like real-world application. Parents can create simple, supervised mini-experiences that serve as teachable moments. These might include:

- Allowing a six-year-old to hand cash to a cashier and receive change, thereby understanding currency value and the exchange process.

- Empowering a seven-year-old to choose an item within a set budget during a shopping trip (e.g., “Here’s $5, you can pick one treat”), fostering decision-making skills and an understanding of limits.

- Participating in school “market day” events, where children create and “sell” simple products using play money, offering an early introduction to entrepreneurship, cost, and profit.

- Opening a simple savings account for a child, often jointly with a parent. Seeing their money in a bank and observing even minimal interest accrual makes the concept of saving tangible and exciting, reinforcing the habit of regular contributions. Research indicates that children with a savings account in their name, even with a small balance, are significantly more likely to develop lasting saving habits and pursue higher education [31] [32].

The overarching principle is that children learn finance most effectively when they are actively involved in practical, guided experiences. Every coin deposited into a piggy bank, every supervised purchase, and every discussion around financial decisions serves as a vital building block in their journey towards comprehensive financial literacy.

2.5 Lifelong Impact: How Early Financial Literacy Shapes Future Behavior

The commitment to cultivating financial literacy in children aged 3-8 is not merely an educational ideal but a strategic investment with profound and long-lasting societal benefits. The evidence increasingly suggests that early financial education forms the bedrock for better financial outcomes, enhanced educational and career trajectories, greater economic inclusion, and the development of responsible citizens. The ultimate goal is to nurture financially capable adults who can navigate economic complexities with confidence and make informed decisions throughout their lives.

2.5.1 Better Financial Outcomes

The most direct benefit of early financial literacy is its correlation with improved adult financial health. While most impact studies often focus on high school financial education, the principles extend to earlier interventions. Longitudinal data from the U.S., for example, reveals that students in states with mandated high school personal finance education demonstrate significantly better financial behaviors as young adults. These include lower credit delinquency rates (1-3% lower) and higher credit scores (often 10-20 point increases by their early 20s) compared to peers in states without such mandates [5]. It stands to reason that children who begin receiving financial education as early as 7 or 8, and continue to benefit from sequential learning throughout their schooling, possess an even longer runway to develop and solidify healthy financial habits. This cumulative advantage can translate into substantial improvements in their financial well-being, including better debt management, increased savings, and wiser investment decisions over their lifetime.

2.5.2 College and Career Readiness

Early financial literacy also profoundly impacts educational and career trajectories. Children who understand the value of saving, the cost of education, and the concept of investing in their future are more likely to pursue higher education or vocational training thoughtfully. Research on Children’s Savings Account (CSA) programs, which often commence in elementary school, highlights this impact. Studies have shown that even a small college savings fund can dramatically increase a child’s likelihood of attending and completing college. Specifically, low-to-moderate-income children with savings designated for college—even amounts under $500—were found to be approximately three times more likely to enroll in college. For those with $500 or more saved, the likelihood of graduation increased by an astonishing four times compared to peers with no savings [31] [32]. The act of saving early not only provides a financial asset but also cultivates a forward-thinking mindset of investing in oneself and one’s future, directly impacting aspirations and achievements.

2.5.3 Economic Inclusion and Mobility

Financial illiteracy exacerbates socioeconomic disparities. Without early guidance, children from less affluent backgrounds may enter adulthood facing a dual disadvantage: a lack of inherited wealth combined with a lack of financial acumen. Early interventions can play a crucial role in bridging this gap, fostering greater economic inclusion and mobility. Programs targeting young children in underserved communities—such as school-based banking initiatives or games designed to teach entrepreneurship—have demonstrated promising results in boosting savings behaviors and cultivating financial confidence [33]. Over time, these micro-level changes can aggregate into macro-level outcomes: higher rates of bank account ownership, reduced vulnerability to predatory lending and scams, and an enhanced capacity to accumulate assets. In essence, financial literacy functions as a form of human capital. Just as early literary skills correlate with higher lifetime earnings, early financial literacy can significantly contribute to greater economic stability and upward mobility for individuals and communities.

2.5.4 Multiplier Effect on Families and Communities

The impact of early financial education extends beyond the individual child, often creating a positive multiplier effect within families and communities. When children are exposed to financial concepts at a young age, their curiosity can prompt financial discussions within the home, potentially encouraging parents to re-evaluate or deepen their own financial knowledge. Some family-oriented financial literacy programs actively encourage children to share their lessons with caregivers. For instance, a 7-year-old learning about needs versus wants at school might spark a family discussion about budgeting for groceries (a need) before discretionary purchases like toys (a want). Over time, financially literate children grow into capable adults who can support their families through informed decisions, such as navigating complex college loan options or avoiding costly debt, reducing the likelihood of their needing financial support themselves. This ripple effect means that early financial education can uplift entire families and contribute to the economic resilience of communities.

2.5.5 Responsible Consumers and Investors

Early exposure to financial concepts cultivates a more discerning and responsible consumer and an informed citizen. Children who learn about the mechanisms of advertising from a young age are more likely to become skeptical teenagers and adults, less susceptible to misleading marketing or “buy now, pay later” schemes. Understanding the power of compound interest through observing their earliest savings grow might inspire them to begin investing strategically in their twenties. On a broader societal scale, a generation steeped in financial literacy from childhood is poised to make more prudent collective decisions. They are likely to be better prepared for retirement, less prone to excessive debt, and more inclined to participate in the economy in healthy and productive ways, such as homeownership or entrepreneurship. These long-term societal benefits, though difficult to quantify precisely year-by-year, underpin the compelling argument for the collaborative efforts of businesses, educators, and policymakers to champion financial literacy from the earliest ages. As an OECD report aptly summarizes, “teaching financial skills early is an investment that pays dividends for life – for individuals, economies, and society at large” [13].

In conclusion, the evidence overwhelmingly supports the assertion that the formative years, particularly ages 3-8, are a critical period for establishing fundamental financial understanding and lifelong money habits. The confluence of early cognitive development, profound parental influence, and the increasing societal recognition of financial literacy as an essential life skill necessitates early intervention. By embracing age-appropriate, play-based learning and integrating financial education into both home and school environments, it is possible to cultivate a generation of financially capable individuals prepared for the complexities of the modern world.

The next section will build on this understanding of early habit formation by exploring the specific developmental milestones and cognitive capacities of children aged 3-8, providing a clearer roadmap for what financial concepts can realistically be taught at each stage of early childhood.

References

[1] PBS NewsHour. (April 5, 2018). Money habits are set by age 7. Teach your kids the value of a dollar now. Retrieved from www.pbs.org

[17] PBS NewsHour. (April 5, 2018). Money habits are set by age 7. Teach your kids the value of a dollar now. Retrieved from www.pbs.org

[8] CardRatings.com. (March 6, 2023). Survey: Early financial education at home matters, but there’s a gender gap. Retrieved from www.cardratings.com

[18] Kids’ Money. (March 20, 2023). Large Global Survey of Students Reveals 59 Percent Want More Financial Literacy Education. Retrieved from www.kidsmoney.org

[19] J-PAL/IPA Study Summary. (2018). Evaluating the efficacy of school-based financial education programs with children in Ghana. Retrieved from www.povertyactionlab.org

[20] Kiplinger. (July 25, 2025). From Piggy Banks to Portfolios: A Financial Planner’s Guide to Talking to Your Kids About Money at Every Age. Retrieved from www.kiplinger.com

[10] CardRatings.com. (March 6, 2023). Survey: Early financial education at home matters, but there’s a gender gap. Retrieved from www.cardratings.com

[21] PBS NewsHour. (April 5, 2018). Money habits are set by age 7. Teach your kids the value of a dollar now. Retrieved from www.pbs.org

[22] CardRatings.com. (March 6, 2023). Survey: Early financial education at home matters, but there’s a gender gap. Retrieved from www.cardratings.com

[23] Kiplinger. (November 8, 2025). Smart Strategies for Paying Your Child an Allowance. Retrieved from www.kiplinger.com

[24] Kiplinger. (November 8, 2025). Smart Strategies for Paying Your Child an Allowance. Retrieved from www.kiplinger.com

[25] Axios. (April 16, 2024). Texas and California among states lacking personal finance education. Retrieved from www.axios.com

[5] Axios. (April 16, 2024). Texas and California among states lacking personal finance education. Retrieved from www.axios.com

[13] Kids’ Money. (March 20, 2023). Large Global Survey of Students Reveals 59 Percent Want More Financial Literacy Education. Retrieved from www.kidsmoney.org

[26] PubMed. (2016). The Impact of Social and Financial Education on Savings Attitudes and Behaviors Among Primary School Children in Uganda. Retrieved from pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

[27] The Atlantic. (December 2025). The New Allowance. Retrieved from www.theatlantic.com

[28] Kiplinger. (November 8, 2025). Smart Strategies for Paying Your Child an Allowance. Retrieved from www.kiplinger.com

[29] The Atlantic. (December 2025). The New Allowance. Retrieved from www.theatlantic.com

[30] No direct citation from research text for “Sesame Street & PNC Bank’s “For Me, For You, For Later” program. Information for this section draws on the detail provided in the extracted text itself.

[31] Wikipedia. Children’s Savings Accounts. Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org

[32] Wikipedia. Children’s Savings Accounts. Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org

[33] PubMed. (2016). The Impact of Social and Financial Education on Savings Attitudes and Behaviors Among Primary School Children in Uganda. Retrieved from pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

3. The Crucial Role of Parents: Home as the First Financial Classroom

The journey toward financial literacy often begins not in a formal classroom, but within the home. Parents, as the primary caregivers and educators during a child’s most formative years, wield significant influence over their children’s understanding and attitudes toward money. Research consistently highlights the profound impact parental engagement has on shaping early money habits, with children as young as three beginning to grasp basic financial concepts, and many core money behaviors firmly established by age seven[1]. This critical developmental window underscores why the home environment is increasingly recognized as the foundational financial classroom, and parents as the inaugural financial educators. Their conversations, examples, and practical tools, such as allowances, lay the groundwork for lifelong financial decision-making.

In recent years, there has been a notable shift in parental recognition of this responsibility. A 2025 global survey revealed that a substantial 72% of parents feel personally responsible for teaching their children about money. Furthermore, an overwhelming 97% reported engaging in financial discussions with their children to some extent[2]. This near-universal acknowledgment signals a positive trend, moving away from past generations where money was often considered a taboo subject. However, this commitment is not without its challenges. While many parents are willing to provide financial education, about 50% of those who issue allowances admit to struggling with explaining financial concepts in a way their children can easily understand[3]. This highlights a crucial gap between intent and effective implementation, emphasizing the need for better resources and strategies to empower parents in this vital role. This section will delve deep into the multifaceted influence of parents, examining their evolving responsibilities, the utility of tools like allowances, the art of effective money conversations, and the imperative to address historical biases to ensure inclusive financial education for all children.

The Foundational Impact of Early Parental Guidance

The earliest years of a child’s life are widely acknowledged as a period of rapid development, where fundamental skills and attitudes are established. This principle extends profoundly to financial literacy. By age three, children demonstrate an understanding of basic money concepts, such as recognizing coins and the principle of exchange. More significantly, by age seven, many of their core money habits – encompassing tendencies toward saving, spending, and financial discipline – are largely entrenched[4]. This scientific consensus, stemming notably from a Cambridge University study cited by PBS NewsHour, dramatically redefines the perceived timeline for financial education, pushing it much earlier than traditionally assumed. Waiting until adolescence or high school to introduce financial concepts, as many curricula do, may prove to be a missed opportunity to shape fundamental behaviors when they are most malleable.

The habits formed in early childhood are particularly resilient and tend to persist into adulthood. For instance, a child who is encouraged to save a portion of their allowance or birthday money from a young age is more likely to develop a lifelong saving habit. Conversely, a lack of early exposure to money management can lead to later challenges. As one expert analogy suggests, just as reading is taught early because literacy builds over years, financial literacy has a “prime learning time” in early childhood for foundational skills[5]. The implication is clear: the cumulative effect of continuous financial education, starting from ages 3-8, grants children a significant advantage in building healthy financial behaviors.

The long-term benefits of this early parental guidance are substantial. Studies have shown that individuals who received financial education, whether at home or in school, tend to exhibit higher savings rates and greater net worth in their late 20s than their peers who did not[6]. This underscores that financial literacy is not merely about understanding complex financial products, but about cultivating strong behavioral patterns early on. The global statistic that only about 33% of adults are considered financially literate highlights a widespread deficiency that many experts believe can be remedied by initiating financial education much earlier in life[7]. Parents are the first line of defense in addressing this deficit, fostering a generation that is more equipped to navigate the complexities of personal finance.

However, it is crucial that this early intervention is age-appropriate. For children aged 3-5, lessons should be concrete and experiential. This might involve recognizing coins, understanding that money is exchanged for goods, or differentiating between needs and wants through simple examples. Introducing abstract concepts like interest rates or mortgages to very young children can be confusing or even counterproductive. The focus should be on play-based learning and gradual introduction. For instance, a study in Ghana found that purely financial lessons, without accompanying social lessons, could inadvertently encourage children to work more at the expense of their schooling, highlighting the importance of balancing financial concepts with broader ethical and social considerations[8]. Therefore, parental guidance must be carefully calibrated to a child’s developmental stage, ensuring that financial education is both effective and holistic.

Parents as Exemplars: Modeling and Money Conversations

Beyond explicit instruction, parents serve as powerful role models, with their own financial behaviors and attitudes profoundly influencing their children. Children observe and absorb lessons from everyday parental actions, whether it’s using a credit card, budgeting during grocery shopping, or withdrawing cash from an ATM. These seemingly mundane activities become invaluable “teachable moments” when accompanied by parental narration and explanation. For example, a parent might articulate, “We’re using this coupon because it helps us save money,” or “I’m paying the electricity bill so we can have lights in our home.” Such commentary helps demystify money, making abstract financial processes tangible and understandable for young minds.

The increasing willingness of parents to openly discuss financial matters marks a significant departure from historical norms. A 2025 Ameriprise survey indicates that 72% of parents now accept personal responsibility for teaching finances, with a striking 97% engaging in some form of money conversation with their children[9]. This contrasts sharply with previous generations, where a notable 18% of adults reported receiving no financial guidance from their parents whatsoever[10]. Modern parents, often driven by the desire to better prepare their children for economic realities, are actively dismantling past taboos surrounding money, transforming the home into a dynamic forum for financial learning.

Regular discussions about budgets, saving goals, and even family financial constraints (articulated in an age-appropriate manner) are crucial. These conversations not only build financial literacy but also foster a sense of shared responsibility and economic realism. Children who regularly engage in financial discussions with their parents tend to score higher on financial literacy assessments as teenagers and report greater confidence in handling money independently[11]. This ongoing dialogue helps children understand the practical applications of financial concepts and cultivates a mindset of prudent management. The informal, continuous nature of these home-based discussions allows for lessons to be reinforced and adapted as a child grows, making them highly effective.

The Allowance as a Practical Teaching Tool

One of the most widespread and effective tools parents employ for hands-on financial education is the allowance. A recent survey revealed that 71% of parents with children aged 5 to 17 provide an allowance, with the average weekly amount being $37[12]. This practice provides children with a structured opportunity to manage their own mini “income” and learn essential skills like budgeting, saving, and spending.

The utility of allowance is maximized when it is intentionally linked to financial lessons. Many families adopt strategies that require children to allocate their allowance into designated categories, often depicted through a system of jars or bank accounts labeled “Spend,” “Save,” and “Donate.” This segmentation visually reinforces the concept of financial planning and encourages children to consider different uses for their money. For instance, the Stern family in San Diego implemented an “earn and learn” system, paying their sons for extra chores beyond their regular responsibilities, thereby establishing a clear link between effort and income[13]. This method not only teaches about earning but also about budgeting, as fluctuating income requires flexible planning for spending and saving. It ingrains the understanding that money is a finite resource often tied to effort, a critical lesson for early financial development. Another important finding from family allowance apps is that kids saved approximately 43% of their allowance on average in 2022, an increase from 38% in 2019[14]. This demonstrates children’s capacity and willingness to save when given the opportunity and structure.